What is Public Narrative?

Learn about public narrative and the power of story from Marshall Ganz. This article includes an analysis of Obama's speech - "The Audacity of Hope".

Introduction

The questions of what am I called to do, what my community is called to do, and what we are called to do now are at least as old as Moses’ conversation with God at the burning bush. Why me? asks Moses, when called to free his people. And, who – or what – is calling me? Why these people? Who are they anyway? And why here, now, in this place?

Practicing leadership – enabling others to achieve purpose in the face of uncertainty – requires engaging the heart, the head, and the hands: motivation, strategy, and action. Through narrative we can articulate the experience of choice in the face of urgent challenge and we can learn how to draw on our values to manage the anxiety of agency, as well as its exhilaration. It is the discursive process through which individuals, communities, and nations make choices, construct identity, and inspire action. Because we use narrative to engage the “head” and the “heart,” it both instructs and inspires – teaching us not only how we ought to act, but motivating us to act – and thus engaging the “hands” as well.

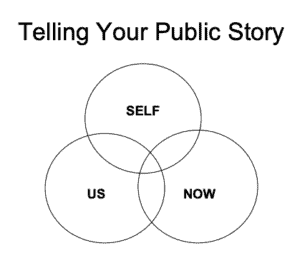

Public narrative is woven from three elements: a story of why I have been called, a story of self; a story of why we have been called, a story of us; and a story of the urgent challenge on which we are called to act, a story of now. This articulation of the relationship of self, other, and action is also at the core of our moral traditions. As Rabbi Hillel, the 1st Century Jerusalem sage put it,

If I am not for myself, who will be for me? If I am for myself alone, what am I? If not now, when? ii

Public narrative is a leadership art. Leaders draw on narrative to inspire action across cultures, faiths, professions, classes, and eras. And as the questions posed by Moses above indicate, public narrative is composed of three elements: a story of self, a story of us, and a story of now. A story of self communicates who I am – my values, my experience, why I do what I do. A story of us communicates who we are – our shared values, our shared experience, and why we do what we do. And a story of now transforms the present into a moment of challenge, hope, and choice.

I first asked myself these questions in 1964, while I was completing my third year at Harvard College. I had become active in the civil rights movement and volunteered for the Mississippi Summer Project. In Mississippi, I found the calling I would pursue for the next 28 years – organizing migrant farm workers, community organizations, trade unions, and electoral politics.

In 1991, in order to deepen my understanding of my work, I returned to Harvard, completed my undergraduate degree, Class of 1964-92, an MPA in 1993, and a Ph.D. in sociology in 2000. When I joined the Kennedy School faculty, I discovered a second calling as a teacher, scholar, and advocate. And I found myself moved by values rooted in the same life experience that had set me on my first path: the work of my parents as rabbi and teacher; our experience of the Holocaust, and growing up with Passover Seders, challenged by the teaching that the journey from slavery to freedom passes from one generation to the next; and the critical eyes and the hopeful hearts of young people.

In recent years, scholars across a wide range of disciplines have engaged in the study of narrative, including psychology, sociology, political science, philosophy, legal studies, theology, literary studies, and the arts. Professions engaged in narrative practice include the military, the ministry, the law, politics, business, and the arts. This approach builds on our native understanding of narrative, its analysis across the disciplines, and its practice across the professions.

Two years ago, convinced that a major challenge we face as individuals, as a culture, and as a nation is to reclaim our capacity to articulate, draw courage from, and act upon, public values, I designed this approach as a way to learn how we can translate our values into action. The pedagogy is rooted in the nature of public narrative: a combination of Self, Other, and Action. We model public narrative, engage in reflection on narrative, learn how to coach one another, and learn how to evaluate based on a practical and analytic understanding of what we are doing. Public narrative is not public speaking. As Jayanti Ravi, one of my students from India put it; the course teaches how to bring out the “glow” from within, rather than how to apply a “gloss” from without.

Values, Motivation and Action

Why & How Psychologist Jerome Bruner argues that we interpret the world in analytic and narrative modes.iii Cognitively mapping the world, we identify patterns, discern connections, test relationships, and hypothesize empirical claims – the domain of analysis. But we also map the world affectively, coding experiences, objects, and symbols as good for bad or us for us, fearful or safe, of hopeful or of depressing, etc. When we consider purposeful action, we ask ourselves two questions: why and how. Analysis helps answer the “how question” – how do we use resources efficiently to detect opportunities, compare costs, etc. But to answer the “why question – why does this matter, why do we care, why do we value one goal over another – we turn to narrative. The why question in not why we think we ought to act, but, rather why we do act, what moves us to act, our motivation, our values. Or, as St. Augustine put it, the difference between “knowing” the good as an ought and “loving the good” as a source of motivation.iv

To understand motivation – that which inspires action – consider the word emotion and their shared root word, motor — to move. Psychologists argue that information provided by our emotions, which we experience as feelings, is partly physiological, as when our respiration changes or our body temperature alters; partly behavioral, as when we are moved to advance or to flee, to stand up or to sit down; and partly cognitive since we can describe what we feel as fear, love, desire, or joy.

We also experience our values through our emotions. Our emotions provide us with vital information about how to live our lives, not in contrast to reasoned deliberation, but more as a precondition for it.1 Moral philosopher Martha Nussbaum argues that because we experience value through emotion, trying to make moral choices without emotional information is futile.v She supports her argument with research on people afflicted with lesions on the amygdale, a part of the brain central to our emotions. When faced with decisions, they can come up with one option after another, but cannot decide because decisions ultimately are based on judgments of value. And if we cannot experience emotion, we cannot experience values that orient us to the choices we must make.

Some emotions inhibit mindful action while others facilitate it. Exploring the relationship between emotion and purposeful action, political scientist George Marcus points to two of our neurophysiologic systems – surveillance and disposition. vi Our surveillance system compares what we expect to see with what we do see, tracking anomalies which, when observed, translate into anxiety.

Without this emotional cue, Marcus argues, we simply operate out of habit. When we do feel anxiety, it is a way of saying to ourselves, “Hey! Pay attention! There’s a bear in the doorway!” The big question is what we do with that anxiety. 1 G. E. Marcus, (2002), The Sentimental Citizen. (University Park, PA, Penn State University Press). Our dispositional system operates along a continuum from depression to enthusiasm, or, as we might also describe it, from despair to hope. So if we experience anxiety in a despairing mode, our fear will kick in, or our rage – neither of which is very adaptive. On the other hand, if we are hopeful, our curiosity is more likely to be triggered, leading to exploration that can yield learning and creative problem solving. So our readiness to consider action, capacity to consider it well, and ability to act on our consideration rests on how we feel.

Leadership requires engaging others in purposeful action by mobilizing feelings that can facilitate it to challenge feelings that inhibit it. This can produce an emotional dissonance, a tension that may only be resolved through action. Organizers call this agitation. For example, my fear of not upsetting the boss (teacher, parent, employer) because of my dependency on him or her may conflict with my sense of self-respect if the boss acts to violate it. One person may become angry enough to challenge her boss; another may “swallow her pride” and another may resist the organizer who points out the conflict. Any of these options is costly, but one may serve a person’s interests better than another.

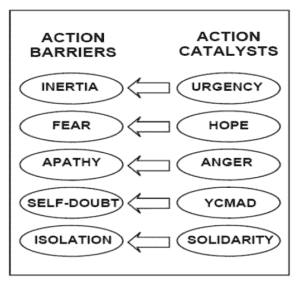

As the chart illustrates, while inertia – the security of habitual routine – can blind us to the signs of a need for action, urgency and sometimes anger get our attention. Fear can paralyze us, driving us to rationalize inaction, amplified by self-doubt and isolation, we may become victims of despair. On the other hand, hope can inspires us and, in concert with self-esteem (you can make a difference) and solidarity (love, empathy), can move us to act.

Urgency that captures our attention, creates the space for new action, but is less about time than it is about priority. The urgent need to complete a problem set due tomorrow, supplants the important need to figure out what to do with the rest of life. The urgent need to attend to a critically ill family member supplants the important need to attend the next business meeting (or ought to?). The urgent need to devote the day turning out voters for a critical election supplants the important need to review the family budget. Commitment and concentration of energy are required to launch anything new, and creating a sense of urgency is often the way to get the focused commitment that is required.

What about inertia’s first cousin, apathy? One way to counter apathy is with anger – not rage, but outrage and indignation with injustice. Constructive anger is grows out of experiencing the difference between what ought to be and what is – the way we feel when our moral order has been violated.vii Sociologist Bill Gamson describes this as using an “injustice frame” to counter a “legitimacy frame.”viii As scholars of “moral economy” have taught us, people rarely mobilize to protest inequality as such, but they do mobilize to protest “unjust” inequality.ix In other words, our values, moral traditions, and sense of personal dignity can function as critical sources of the motivation to act.

Where can we find the courage to act in spite of fear? Trying to eliminate that which we react to fearfully is a fool’s errand because it locates the source of our fear outside ourselves, rather than within our own hearts.

Trying to make ourselves “fearless” is counterproductive if it means acting more out of “nerve than brain.” Leaders can “inoculate” by warning others that the opposition will threaten them with this and woo them with that. The fact that these behaviors are expected reveals the opposition as more predictable and thus less to be feared. But in reality, it is the choice to act in spite of fear that is the meaning of courage. And of the emotions that help us find courage, perhaps most important is hope.

Where do we go to get some hope? One source of hope is the experience of “credible solutions”, reports not only of success elsewhere, but direct experience of small successes and small victories. Another important source of hope for many is in faith traditions, grounded in spiritual beliefs, cultural traditions, and moral understandings. Many of the great social movements – Gandhi, Civil Rights, and Solidarity — drew strength from religious traditions, and much of today’s organizing occurs in faith communities. Relationships offer another source of hope. We all know people who inspire hopefulness just by being around them. “Charisma” can be seen as the capacity to inspire hope in others, inspiring others to believe in themselves.

Psychologists who have begun to explore the role of “positive emotions” give particular attention to the “psychology of hope.”x More philosophically, Moses Maimonides, the Jewish scholar of the 12th Century, argued that hope is belief in the “plausibility of the possible” as opposed to the “necessity of the probable.”xi

Leaders counter self-doubt by attending to the self-efficacy of others, creating the sense that you can make a difference, or YCMAD. One way to inspire this sentiment is to frame action in terms of what people can do, not what they can’t do. If an organizer designs a plan calling for each new volunteer to recruit 100 people and provides no leads, training or coaching, s/he will only create deeper feelings of self-doubt. Recognition based on real accomplishment, not empty flattery, can help, meaning there is no real recognition without accountability. Accountability does not show lack of trust, but is evidence that what one is doing really matters.

Finally, leaders can counter feelings of isolation with the experience of belovedness or solidarity. This is the role of mass meetings, celebration, singing, common dress, and shared language.

The way we feel about things, however, may have little to do with the present, but rather is a legacy of lessons learned long ago. Suppose that, as a four-year-old, you are playing on a swing-set at the park when a bigger kid tries to kick you off. You run to your parent for help, but your parent laughs it off. In that moment you are angry and embarrassed, convinced that your parent doesn’t care. You now have learned the lesson that counting on others is a bad idea. As an adult, evaluating what to do about a pay cut, your past experience will make it unlikely that you will join other workers to protest. You fear counting on others; you may even tell yourself you deserved that pay cut. If you are still in the grips of that fear when an organizer comes along and tells you that, with a union, you could keep the employer from cutting your pay, you will see that organizer as a threat, her claims suspect and her proposals hopeless.

So exercising leadership often requires engaging in an emotional dialogue, drawing on one set of emotions (or values) which are grounded in one set of experiences, in order to counter another set of emotions (or values), grounded in different experiences – a dialogue of the heart. This dialogue of the heart, far from being irrational, can restore choices that have been abandoned in despair.

The Power of Story

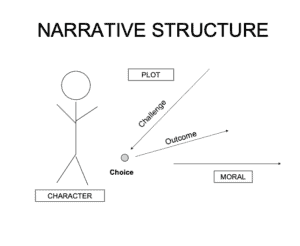

The discursive form through which we translate values into action is story. A story is crafted of just three elements: plot, character, and moral. The effect depends on the setting: who tells the story, who listens, where they are, why they are there, and when.

Plot

A plot engages us, captures our interest, and makes us pay attention. “I got up this morning, had breakfast, and came to school.” Is that a plot? Why? Why not?

How about: “I was having breakfast this morning when I heard a loud screeching coming from the roof. At that very moment I looked outside to where my car was parked, but it was gone!!!” Now what’s going on? What’s the difference?

A story begins. An actor is moving toward a desired goal. But then some kind of challenge appears. The plan is suddenly up in the air. The actor must figure out what to do. This is when we get interested. We want to find out what happens.

Why do we care?

Dealing with the unexpected – small and large – defines the texture of our lives. No more tickets at the movie theater. You’re about to lose your job. Our marriage is on the verge of breakup. We are constantly faced with the unexpected, and what we’re going to do. And what is the source of the greatest uncertainty around us? Other people. The subject of most stories is about how to interact with other people.

As human beings we make choices in the present, based on remembering the past and imagining the future. This is what it means to be an agent. But when we act out of habit, we don’t choose; we just follow the routine. It is only when the routines break down, when the guidelines are unclear, when no one can tell us what to do, that we make real choices and become the creators of our own lives, communities, and futures. Then we become the agents of our own fate. These moments can be as frightening as they are exhilarating.

A plot consists of just three elements: a challenge, a choice, and an outcome. Attending to plot is how we learn to deal with the unpredictable. Researchers report that most of the time that parents spend with young children is in story telling – stories of the family, the child’s stories, stories of the neighbors. Bruner describes this as agency training: the way we learn how to process choices in the face of uncertainty. And because our curiosity about the unexpected is infinite, we invest billions of dollars and countless hours in films, literature and sports events – not to mention religious practices, cultural activities, and national celebrations.

Character

Although a story requires a plot, it only works if we can identify with a character. Through our empathetic identification with a protagonist, we experience the emotional content of the story. That is how we learn what the story has to teach to our hearts, not only our heads. As Aristotle wrote of Greek tragedy, this is how the protagonist’s experience can touch us and, perhaps, open our eyes.xii Arguments persuade with evidence, logic, and data. Stories persuade by this empathetic identification. Have you ever been to movie where you couldn’t identify with any of the characters? It’s boring. Sometimes we identify with protagonists that are only vaguely “like us” – like the road runner (if not the coyote) in the cartoons. Other times we identify with protagonists that are very much like us – as in stories about friends, relatives, neighbors. Sometimes the protagonists of a story are us, as when we find ourselves in the midst of an unfolding story, in which we are the authors of the outcome.

Moral

Stories teach. We’ve all heard the ending – “and that is the moral of the story.” Have you ever been at a party where someone starts telling a story and they go on…and on…and on…? Someone may say (or want to say), “Get to the point!” We deploy stories to make a point, and to evoke a response. The moral of a successful story is emotionally experienced understanding, not only conceptual understanding, and a lesson of the heart, not only the head. When stated only conceptually, many a moral becomes a banality. Saying “haste makes waste” does not communicate the emotional experience of losing it all because we moved too quickly – but it can remind of that feeling, learned through a story. Nor can we expect morals to provide detailed tactical information. We do not retell the story of David and Goliath because it teaches us how to use a slingshot. What the story teaches is that a “little guy” – with courage, resourcefulness, and imagination – can beat a “big guy,” especially one with Goliath’s arrogance. We feel David’s anger, courage, and resourcefulness and feel hopeful for our own lives because he is victorious. Stories thus teach how to manage our emotions, not repress them, so we can act with agency to face our own challenges.

Stories teach us how to act in the “right” way. They are not simply examples and illustrations. When they are well told, we experience the point, and we feel hope. It is that experience, not the words as such, that can move us to action. Because sometimes that is the point – we have to act.

Setting

Stories are told. They are not a disembodied string of words, images, and phrases. They are not messages, sound bites, or brands – although these rhetorical fragments may reference a story. Storytelling is fundamentally relational. As we listen, we evaluate the story, and we find it more or less easy to enter, depending on the storyteller.

- Is it his or her story? We hear it one way.

- Is it the story of a friend, a colleague, or a family member? We hear it another way.

- Is it a story without time, place, or specificity? We step back.

- Is it a story we share, perhaps a Bible story? Perhaps we draw closer to one another. Storytelling is how we interact with each other about values; how we share experiences with each other, counsel each other, comfort each other, and inspire each other to action.

Public Narrative: Self, Us, Now

Leadership, especially leadership on behalf of social change, often requires telling a new public story, or adapting an old one: a story of self, a story of us, and a story of now. A story of self communicates the values that are calling you to act. A story of us communicates values shared by those whom you hope to motivate to act. And a story of now communicates the urgent challenge to those values that demands action now. Participating in a social action not only often involves a rearticulation of one’s story of self, us, and now, but marks an entry into a world of uncertainty so daunting that access to sources of hope is essential. To illustrate, I’ll draw examples from the first seven minutes of Sen. Barack Obama’s speech to the Democratic National Convention in July 2004 (see appendix).

Telling Your Public Story – Story of Self

Telling one’s story of self is a way to share the values that define who you are — not as abstract principles, but as lived experience. We construct stories of self around choice points – moments when we faced a challenge, made a choice, experienced an outcome, and learned a moral. We communicate values that motivate us by selecting from among those choice points, and recounting what happened. Because story telling is a social transaction, we engage our listener’s memories as well as our own as we learn to adapt our story of self in response to feedback so the communication is successful. Similarly, like the response to the Yiddish riddle that asks who discovered water: “I don’t know, but it wasn’t a fish.” The other person often can “connect the dots” that we may not have connected because we are so within our own story that we have not learned to articulate them.

We construct our identity, in other words, as our story. What is utterly unique about each of is not a combination of the categories (race, gender, class, profession, marital status) that include us, but rather, our journey, our way through life, our personal text from which each of us can teach.

A story is like a poem. It moves not by how long it is, nor how eloquent or complicated. It moves by offering an experience or moment through which we grasp the feeling or insight the poet communicates. The more specific the details we choose to recount, the more we can move our listeners, the more powerfully we can articulate our values, what moral philosopher Charles Taylor calls our “moral sources.” xiii Like a poem, a story can open a portal to the transcendent.

Telling about a story is different from telling a story. When we tell a story we enable the listener to enter its time and place with us, see what we see, hear what we hear, feel what we feel. An actor friend once told me the key was to speak entirely in the present tense and avoid using the word “and”: I step into the room. It is dark. I hear a sound. Etc.

Some of us may think our personal stories don’t matter, that others won’t care, or that we should talk about ourselves so much. On the contrary, if we do public work we have a responsibility to give a public account of ourselves – where we came from, why we do what we do, and where we think we’re going. In a role of public leadership, we really don’t have a choice about telling our story of self. If we don’t author our story, others will – and they may tell our story in ways that we may not like. Not because they are malevolent, but because others try to make sense of who by drawing on their experience of people whom they consider to be like us.

Aristotle argued that rhetoric has three components – logos, pathos, and ethos – this is ethos.xiv The logos is the logic of the argument. The pathos is the feeling the argument evokes. The ethos is the credibility of the person who makes the argument. – their story of self.

Social movements are often the “crucibles” within which participants learn to tell new stories of self as we interact with other participants. Stories of self can be challenging because participation in social change is often prompted by a “prophetic” combination of criticality and hope. In personal terms this means that most participants have stories both of the world’s pain and the world’s hope. And if we haven’t talked about our stories of pain very much, it can take a while to learn to manage it. But if others try to make sense of why we are doing what we are doing – and we leave this piece out – our account will lack authenticity, raising questions about the rest of the story.

In the early days of the women’s movement, people participated in “consciousness raising” group conversations which mediated changes in their stories of self, who they were, as a woman. Stories of pain could be shared, but so could stories of hope. In the civil rights movement, Blacks living in the Deep South who feared claiming the right to vote, had to encourage one another to find the courage to make the claim – which, once made, began to alter how they thought of themselves, how they could interact with their children, as well as with white people, and each other.

In Sen. Obama’s “story of self” he recounts three key choice points: his grandfather’s decision to send his son to America to study, his parent’s “improbable” decision to marry, and his parent’s decision to name him Barack, blessing, an expression of faith in a tolerant and generous America. Each choice communicates courage, hope, and caring. He tells us nothing of his resume, preferring to introduce himself by telling us where he came from, and who made him the person that he is, so that we might have an idea of where he is going.

Story of Us

Our stories of self overlap with our stories of us. We participate in many us’s: family, community, faith, organization, profession, nation, or movement. A story of us expresses the values, the experiences, shared by the us we hope to evoke at the time. A story of “us” not only articulates the values of our community; it can also distinguish our community from another, thus reducing uncertainty about what to expect from those with whom we interact. Social scientists often describe a “story of us” as a collective identity.xv

Our cultures are repositories of stories. Stories about challenges we have faced, how we stood up to them, and how we survived are woven into the fabric of our political culture, faith traditions, etc. We tell these stories again and again in the form of folk sayings, songs, religious practice, and celebrations (e.g., Easter, Passover, 4th of July). And like individual stories, stories of us can inspire, teach, offer hope, advise caution, etc. We also weave new stories from old ones. The Exodus story, for example, served the Puritans when they colonized North America, but it also served Southern blacks claiming their civil rights in the freedom movement.

For a collection of people to become an “us” requires a story teller, an interpreter of shared experience In a workplace, for example, people who work beside one another but interact little, don’t linger after work, don’t arrive early, and don’t eat together never develop a story of us. In a social movement, the interpretation of the movement’s new experience is a critical leadership function. And, like the story of self, it is built from the choices points – the founding, the choices made, the challenges faced, the outcomes, the lessons it learned.

In Sen. Obama’s speech, he moves into his “story of us” when he declares, “My story is part of the American story”, and proceeds to lift of values of the American he shares with his listeners – the people in the room, the people watching on television, the people who will read about the next day. And he begins by going back to the beginning, to choices made by the founders to begin this nation, a beginning that he locates in the Declaration of Independence, a repository of the value of equality, in particular. He then sites a series of moments that evoke values shared by his audience.

Story of Now

A story of now articulates an urgent challenge – or threat – to the values that we share that demands action now. What choice must we make? What is at risk? And where’s the hope? In a story of now, we are the protagonists and it is our choices that shape the outcome. We draw on our “moral sources” to find the courage, hope, empathy perhaps to respond. A most powerful articulation of a story of now was Dr. King’s talk delivered in Washington DC on August 23, 1963, often recalled as the “I have a dream” speech. People often forget that what preceded the dream was a nightmare: the consequence of white America’s failure to make good on its promissory note to African Americans. King argued the moment was possessed of the “fierce urgency of now” because this debt could no longer be postponed.xvi If we did not act, the nightmare would only grow worse – for all of us – never to become the dream.

In a story of now, story and strategy overlap because a key element in hope is a strategy – a credible vision of how to get from here to there. The “choice” offered cannot be something like “we must all choose to be better people” or “we must all choose to do any one of this list of 53 things” (which makes each of the trivial). A meaningful choice is more like “we all must all choose – do we commit to boycotting the busses until they desegregate or not?” Hope is specific, not abstract. What’s the vision? When God inspires the Israelites in Exodus, he doesn’t offer a vague hope of “better days”, but describes a land “flowing with milk and honey”xvii and what must be done to get there. A vision of hope can unfold a chapter at a time. It can begin by getting that number of people to show up at a meeting that you committed to do. You can win a “small” victory that shows change is possible. A small victory can become a source of hope if it is interpreted as part of a greater vision. In churches, when people have a “new story” to tell about themselves, it is often in the form of “testimony” – a person sharing an account of moving from despair to hope, the significance of the experience strengthened by the telling of it.

Hope is not to be found in lying about the facts, but in the meaning we give to the facts. Shakespeare’s King Henry V stirs hope in his men’s hearts by offering them a different view of themselves. No longer are they a few bedraggled soldiers led by a young and inexperienced king in an obscure corner of France who is about to be wiped out by an overwhelming force. Now they are a “happy few,” united with their king in solidarity, holding an opportunity to grasp immortality in their hands, to become legends in their own time, a legacy for their children and grand children.xviii This is their time! The story of now is that moment in which story (why) and strategy (how) overlap and in which, as poet Seamus Heaney writes, “Justice can rise up, and hope and history rhyme.”xix And for the claim to be credible, the action must begin right here, right now, in this room, with action each one of us can take. It’s the story of a credible strategy, with an account of how — starting with who and where we are, and how we can, step by step, get to where we want to go. Our action can call forth the actions of others, and their actions can call others, and together these actions can carry the day. It’s like the old protest song Pete Seeger used to sing:

One man’s hands can’t tear a prison down.

Two men’s hands can’t tear a prison down.

But if two and two and fifty make a million,

We’ll see that day come round.

We’ll see that day come round. 2

Sen.Obama’s moves to his “story of now” with the phrase, “There is more work left to do.” After we have shared in the experience of values we identify with America at its best, he confronts us with the fact that they are not realized in practice. He then tells stories of specific people in specific places with specific problems. As we identify with each of them, our empathy reminds of pain we have felt in our own lives. But, he also reminds us, all this could change. And we know it could change. And it could change because we have a way to make the change, if we choose to take it. And that way is to support the election of Sen. John Kerry.

Although that last part didn’t’ work out, the point is that he concluded his story of now with a very specific choice he calls upon us to make.

Through public narrative leaders – and participants – can move to action by mobilizing sources of motivation, constructing new shared individual and collective identities, and finding the courage to act.

Celebrations

We do much of our storytelling in celebrations. A celebration is not a party. It is a way that members of a community come together to honor who they are, what they have done, and where they are going — often symbolically. Celebrations may take place at times of sadness, as well as times of great joy. Celebrations provide rituals that allow us to join in enacting a vision of our community — at least in our hearts. Institutions that retain their vitality are rich in celebrations. In the Church, for example, Mass is “celebrated.” Harvard’s annual celebration is called Graduation and lasts an entire week.

Storytelling is at its most powerful at beginnings — for individuals, their childhood; for groups, their formation; for movements, their launching; and for nations, their founding. Celebrations are a way we interpret important events, recognize important contributions, acknowledge a common identity, and deepen our sense of community. The way that we interpret these moments begins to establish norms, create expectations, and shape patterns of behavior, which then influence all subsequent development. And we draw on them again and again. Nations institutionalize their founding story as a renewable source of guidance and inspiration. Most faith traditions enact a weekly retelling of their story of redemption, usually rooted in their founding. Well-told stories help turn moments of great crises into moments of “new beginnings.”

Conclusion

Narrative allows us to communicate the values that motivate the choices that we make. Narrative is not talking “about” values; rather narrative embodies and communicates values. And it is through the shared experience of our values that we can engage with others, motivate one another to act, and find the courage to take risks, explore possibility and face the challenges we must face.

Appendix

Sen. Barack Obama, “The Audacity of Hope”, Democratic National Convention, Boston, MA, July 27, 2004.

Thank you so much. Thank you. Thank you. Thank you so much. Thank you so much. Thank you. Thank you. Thank you, Dick Durbin. You make us all proud.

On behalf of the great state of Illinois, crossroads of a nation, Land of Lincoln, let me express my deepest gratitude for the privilege of addressing this convention.

Tonight is a particular honor for me because, let’s face it, my presence on this stage is pretty unlikely. My father was a foreign student, born and raised in a small village in Kenya. He grew up herding goats, went to school in a tin-roof shack. His father — my grandfather — was a cook, a domestic servant to the British.

But my grandfather had larger dreams for his son. Through hard work and perseverance my father got a scholarship to study in a magical place, America, that shone as a beacon of freedom and opportunity to so many who had come before.

While studying here, my father met my mother. She was born in a town on the other side of the world, in Kansas. Her father worked on oil rigs and farms through most of the Depression. The day after Pearl Harbor my grandfather signed up for duty; joined Patton’s army, marched across Europe. Back home, my grandmother raised a baby and went to work on a bomber assembly line. After the war, they studied on the G.I. Bill, bought a house through F.H.A., and later moved west all the way to Hawaii in search of opportunity.

And they, too, had big dreams for their daughter. A common dream, born of two continents.

My parents shared not only an improbable love; they shared an abiding faith in the possibilities of this nation. They would give me an African name, Barack, or ”blessed,” believing that in a tolerant America your name is no barrier to success. They imagined — They imagined me going to the best schools in the land, even though they weren’t rich, because in a generous America you don’t have to be rich to achieve your potential.

They’re both passed away now. And yet, I know that on this night they look down on me with great pride.

They stand here — And I stand here today, grateful for the diversity of my heritage, aware that my parents’ dreams live on in my two precious daughters. I stand here knowing that my story is part of the larger American story, that I owe a debt to all of those who came before me, and that, in no other country on earth, is my story even possible.

Tonight, we gather to affirm the greatness of our Nation — not because of the height of our skyscrapers, or the power of our military, or the size of our economy. Our pride is based on a very simple premise, summed up in a declaration made over two hundred years ago:

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.

That is the true genius of America, a faith — a faith in simple dreams, an insistence on small miracles; that we can tuck in our children at night and know that they are fed and clothed and safe from harm; that we can say what we think, write what we think, without hearing a sudden knock on the door; that we can have an idea and start our own business without paying a bribe; that we can participate in the political process without fear of retribution, and that our votes will be counted — at least most of the time.

This year, in this election we are called to reaffirm our values and our commitments, to hold them against a hard reality and see how we’re measuring up to the legacy of our forbearers and the promise of future generations.

And fellow Americans, Democrats, Republicans, Independents, I say to you tonight: We have more work to do — more work to do for the workers I met in Galesburg, Illinois, who are losing their union jobs at the Maytag plant that’s moving to Mexico, and now are having to compete with their own children for jobs that pay seven bucks an hour; more to do for the father that I met who was losing his job and choking back the tears, wondering how he would pay 4500 dollars a month for the drugs his son needs without the health benefits that he counted on; more to do for the young woman in East St. Louis, and thousands more like her, who has the grades, has the drive, has the will, but doesn’t have the money to go to college.

Now, don’t get me wrong. The people I meet — in small towns and big cities, in diners and office parks — they don’t expect government to solve all their problems. They know they have to work hard to get ahead, and they want to. Go into the collar counties around Chicago, and people will tell you they don’t want their tax money wasted, by a welfare agency or by the Pentagon. Go in – – Go into any inner city neighborhood, and folks will tell you that government alone can’t teach our kids to learn; they know that parents have to teach, that children can’t achieve unless we raise their expectations and turn off the television sets and eradicate the slander that says a black youth with a book is acting white. They know those things.

People don’t expect — People don’t expect government to solve all their problems. But they sense, deep in their bones, that with just a slight change in priorities, we can make sure that every child in America has a decent shot at life, and that the doors of opportunity remain open to all.

They know we can do better. And they want that choice. In this election, we offer that choice.

Our Party has chosen a man to lead us who embodies the best this country has to offer. And that man is John Kerry.

References

See PDF for list of references.

Download PDF

Explore Further

- Why Stories Matter: The Art and Craft of Social Change

- Marshall Ganz: The Power of Storytelling – In dialogue with Walter Link [Video and transcript]

- Barack Obama’s 2004 Democratic National Convention Keynote Speech (Video – Story of Self, Us, Now)

Topics: Tags: Language: