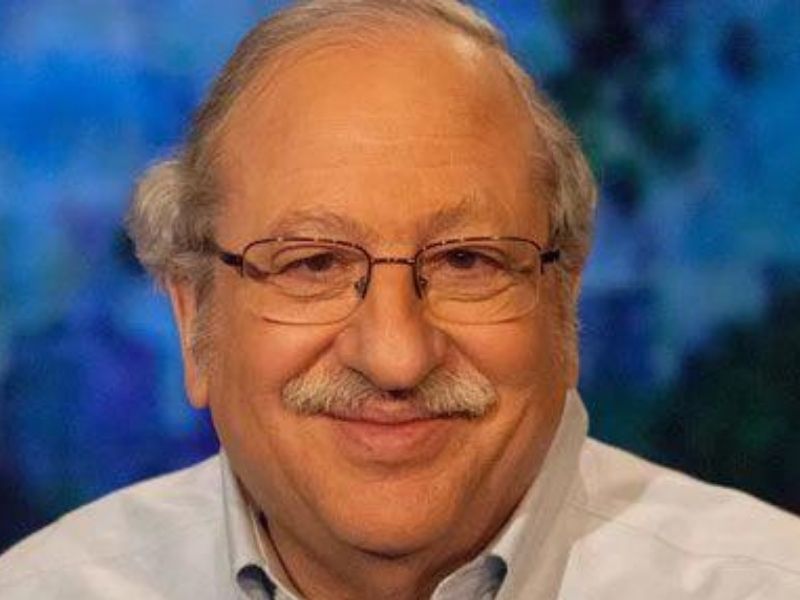

Marshall Ganz

Ruminating with MARSHALL GANZ

About Freedom Summer, working with Cesar Chavez and the power of organizing.

(You can subscribe to Jonathan Alter’s Old Goats newsletter, paid or free, and get other good interviews and columns by clicking here)

I met Marshall Ganz when researching my first Obama book, which was mostly about Obama’s debut in office but also examined how he built the largest and most powerful campaign organization in American history. Ganz was present at the creation. In the summer of 2007, he helped train early Obama organizers at “Camp Obama” in Burbank. Raised mostly in California, Ganz dropped out of Harvard in 1964 and moved to Mississippi to work in the civil rights movement at a crucial moment. He then spent 16 years with Cesar Chavez’ United Farm Workers, where he spearheaded the boycott of grapes and lettuce, before helping California politicians like Jerry Brown and Nancy Pelosi win office. In 1991, he returned to Harvard to finish his degree and become a lecturer at the Kennedy School of Government, where he teaches legendary courses on organizing and public narrative. I asked him about all of that, plus the latest news on the organizing campaign at Amazon.

JONATHAN ALTER:

How did the whole Camp Obama organizing start?

MARSHALL GANZ:

It started with Howard Dean in 2003. At first, they were just doing canvassing and voter ID and the usual stuff. But we got Dean to actually organize—which is a different thing— and build a terrific grassroots organization in New Hampshire and we trained a bunch of people in how to do house meeting organizing.

In 2007, we started organizing early for Obama. The good thing about Camp Obama was we really invested heavily in training. And everything that came afterwards [in the legendary Obama field organization] had a coaching structure with sustained support. It wasn’t a command-and-control structure; it was a team-based structure where volunteers could work with each other. And it became both very motivational and very accountable. It was a really, really good thing.

JON:

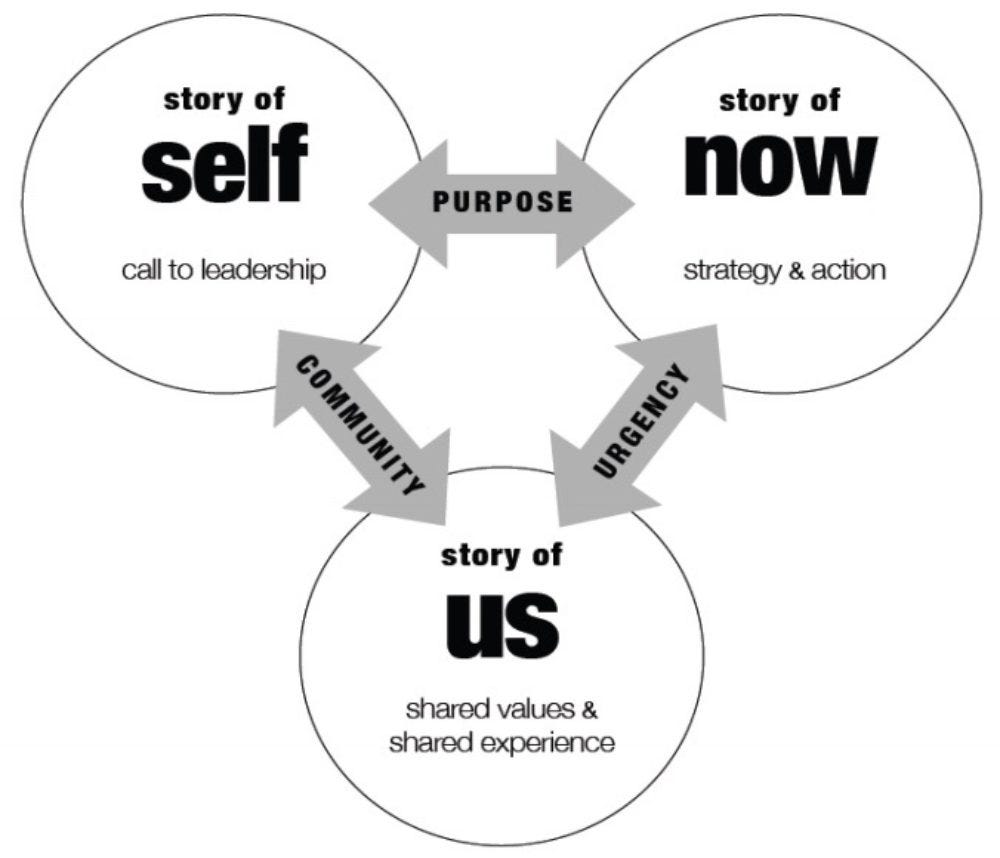

Your idea of people connecting by telling voters and each other stories about their lives helped create a public narrative about Obama and really caught on. But eventually you fell out with the Obama high command.

MARSHALL GANZ:

Obama had a lot of faith in— quote— “the pros.”

JON:

That’s kinda surprising for a former community organizer. What was the difference between the way you wanted to organize and the way that the pros want to organize?

MARSHALL GANZ:

Pros like voter ID and canvassing. They don’t invest in leadership development. They don’t build organization. They don’t invest volunteers with real responsibility. Everything’s turned into a deployment or mobilization. But nothing is invested in actually building leadership in those communities that can take responsibility for doing education, get out the vote and all the rest.

Where this stuff really works, it takes craft.

JON:

Rep. Jamie Raskin is trying to expand the “Democracy Summer” camps that he used in earlier congressional campaigns. Is there enough time this year to have an impact on the midterms by building an organization of people who are passionate about democracy?

MARSHALL GANZ:

That’s a great question. It depends on what they’re really doing. By radically reducing the cost of information, digital technology has facilitated mobilizing. But there are consequences. Take the huge 2011 Egyptian demonstrations in Tahrir Square. The young people who did the mobilizing didn’t build organization at the same time. And that’s why the Muslim Brotherhood— who had organization—came along and prevailed [until a military coup].

JON:

So mobilizing, you can do faster. It’s dramatic, but it’s not as long-lasting as organizing. Is that a fair summary?

MARSHALL GANZ:

Yes. Mobilizing is all about aggregating individuals to show up someplace at some time or do something. But people don’t commit to each other. So it isn’t creating collective capacity. It’s not creating organization. If you’re motivated, you will show up or not, but there’s no infrastructure built. And what we’re missing in this country are democratic infrastructures. It’s a huge problem.

JON:

My sense is that right now the threat to democracy itself is a terrific way to build democratic capacity, infrastructure, and leadership. If somebody would just organize democracy clubs all over the country, I think a lot of Democrats would join. Fear of Trump getting back in, disgust with Republicans suppressing the vote and acting obnoxious and extreme, support for Ukraine—these are motivating issues, if not for voters at large then at least for hundreds of thousands of potential Democratic volunteers.

Tell me if I’m wrong, but isn’t there a third way between Camp Obama organizing and the consultants—‘the pros”— some combination of organizing and mobilizing that could help Democrats defy the odds this fall?

MARSHALL GANZ:

That’s what we have to work toward.

JON:

OK. let’s talk about you. Your father was a rabbi and your mother was a teacher. So how did that affect you growing up?

MARSHALL GANZ:

We lived in Germany for three years after the Second World War when my father was a chaplain in the American army. A lot of his work was with Holocaust survivors. My fifth birthday party was held in an all children’s DP [Displaced Persons] camp. I was to give gifts rather than get them. I thought it was cool until I realized why it was all children: the parents were “gone.” So that was all there for me early on. My [grandmother] was with us and her brother had been sent to Auschwitz. At the same time, my mother, a teacher, loved learning, was excited to be in Europe, so she took us everywhere. When we came back to D.C., things got rough. My father, later diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia, had a very hard time as a congregational rabbi and was simply not available to me. And not my mom, either, though she was the one who really opened my eyes to the whole civil rights thing. So it was a pretty tough period. I developed a lot of anger about this and a sense of outsiderness, but also an enthusiasm for exploration and learning. Soon, my anger was more and more directed at the arbitrary use of power and people being vulnerable to bullying.

Our consciousness of anti-Semitism seemed to factor into the race stuff in a really important way. The religious sensibility was really important when I got into these movements. I was able to engage with Black Christians in the South. I knew Scripture. And I was able to engage with Mexican Catholicism because of having that religious sensibility. That was a huge gift. It was very different for my red diaper friends [activists raised as communists].

JON:

When you’re almost done with Harvard in 1964, you drop out. Why?

MARSHALL GANZ:

A few of us from Harvard were invited to Atlanta (SNCC headquarters) where we were to learn how to get Harvard to withdraw its investments in Mississippi Power and Light Company. While there I got to go to a SNCC [Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee] staff meeting at Gammon Theological Seminary [in Atlanta]. I thought the walls would be covered with maps, strategic models, etc. But they were having a preach-off.

JON:

What’s that?

MARSHALL GANZ:

That’s where they would try to see who could imitate Dr. King better. It was funny and it was celebratory—a combination of joy and courage. And there was joy and courage in dealing with all this crap around them. There was awful shit. The meeting was really appealing. It wasn’t so much “I feel sorry for these poor people.” I admired the young people who were fighting! How could you not want to be part of that?

JON:

Was it a hard decision for you to go to Mississippi after you heard that those three civil rights workers had been killed?

MARSHALL GANZ:

It was scary, for damn sure. But I was committed. And I didn’t want to flake out. You know, courage is often not about being fearless. It’s about finding the resources to carry on. If I had not been part of that community, it wouldn’t have worked.

“You know, courage is often not about being fearless. It’s about finding the resources to carry on.”

It was like Band of Brothers—and sisters. And you could see the change in the communities, in the people—not just a law gets passed in Washington but people finding sources of courage that they hadn’t found before, people trusting one another that hadn’t, people taking risks that they hadn’t before. And to me, that was deeply inspiring and it turned out it was also a way that I could develop my own agency by developing the agency of others. I wouldn’t have put it in these terms, but it was kind of like the insider-outsider—being in the community, but not of it. It goes back to the [Saul] Alinsky idea of the organizer as a kind of stranger. And it turned out to be a thing that worked for me.

JON:

There were 24 bombings in Macomb [Mississippi, population 12,000] in one fall while you’re living there. Did you wake up every morning thinking you’re gonna maybe die that day?

MARSHALL GANZ:

No. You have this capacity to normalize. Everybody’s got everybody else’s back. And down there, white became scary and Black became safe. Anything associated with the white community was scary as hell. And anything associated with the Black community was very safe and very warm and supportive.

In Mississippi, it was group living. There were freedom houses and food donations and money for gas and it’s just subsistence—$10 a week salary. But when you’d walk into a Black bar or restaurant you didn’t pay for anything.

JON:

Would you say you were Jewish?

MARSHALL GANZ:

I would and it was okay. It would be puzzling for people who hadn’t met a Jew before. It was harder later with the Mexican farm workers because so many Catholics had been taught in those days that Jews killed Christ. The anti-Semitism was much clearer than with the Baptists.

JON:

What was your job in Mississippi?

MARSHALL GANZ:

The first summer [1964], I mostly worked to help organize the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party. That was in anticipation of the Democratic Convention in Atlantic City. [Where activists like Fannie Lou Hamer protested the all-white Mississippi delegation]. We went there with lots of hope. But [President] Johnson called a press conference, right in the middle of Mrs. Hamer’s testimony before the credential committee and much of all the support we had started evaporating. Hubert Humphrey [soon to be the vice-presidential nominee] came to town as Johnson’s guy to stop the whole thing.

JON:

Yeah, it was Walter Mondale who worked out the compromise.

MARSHALL GANZ:

Edith Green [a liberal congresswoman from Oregon], Dr. King, and almost everyone else recommended they take the compromise, except for Bob Moses, who drew the distinction between symbolic power and sharing power. He argued that they were being offered symbols but not a share.

Some [activists] actually checked out at that point, some went to the Vietnam [protest movement]. I went back to Mississippi for another year in Macomb. Bob [Moses] left SNCC and that was a shock. After Bob left, a kind of leadership vacuum opened up in SNCC eventually leading to its fracturing and transformation.

JON:

When Bob Moses died, I caught up on some of his amazing accomplishments. What happened to the SNCC leadership after he left?

MARSHALL GANZ:

John [Lewis] was there for a while and left. James Forman was the executive secretary and would have had the job with John, but by that point, things were getting very fractured. There was racial tension,to be sure, agitated by the large number of white volunteers involved in the Summer Project, but also this tension about what are we were supposed to be doing. SNCC had been supporting the development of organizations like Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, and later the Lowndes County Freedom Organization, but it was basically a network of organizers that operated as a small group with leadership everyone knew. Now, it got bigger and more racially complex and we experienced some defeats. Bob was one of the very few people who could cross all those constituencies.

JON:

What was the cause of the tension between SNCC and SCLC [King’s organization]?

MARSHALL GANZ:

There had been tension over the Mississippi Summer Project itself, because the deal cut with Johnson was about the Civil Rights Act [of 1964], which didn’t include voting rights. The SNCC leadership said, “No, this is not cool.” And so they wanted to create something to press the point, which was the Summer Project. Whereas, King’s people didn’t want that to happen. They didn’t want to do anything that would threaten Johnson’s reelection.

JON:

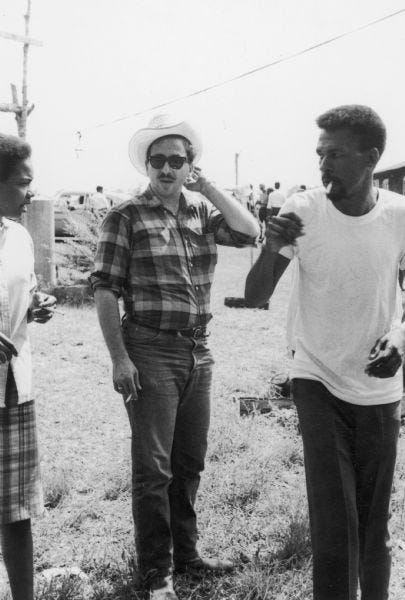

When did you decide you’re going to leave Mississippi and go back to California and work for Chavez?

MARSHALL GANZ:

Once the Voting Rights Act came and we saw the Federal registrars up in the county courthouse, which had been the center of all evil. There was a guy named Ben Faust, all hunched over and born a slave. He claimed to be 105 and said he wanted to do one thing before he died, which was register to vote. And the next morning I got to go up to that courthouse with that guy. It was incredible.

You know, Paul Tillich wrote this book, Love, Power and Justice, in which he says that power without love can never be just, but love without power can never achieve justice. And these were justice fighters. And so inspiring. In Mississippi, I learned the difference between charity and justice. This was never in the spirit of charity. It was fighting for justice.

JON:

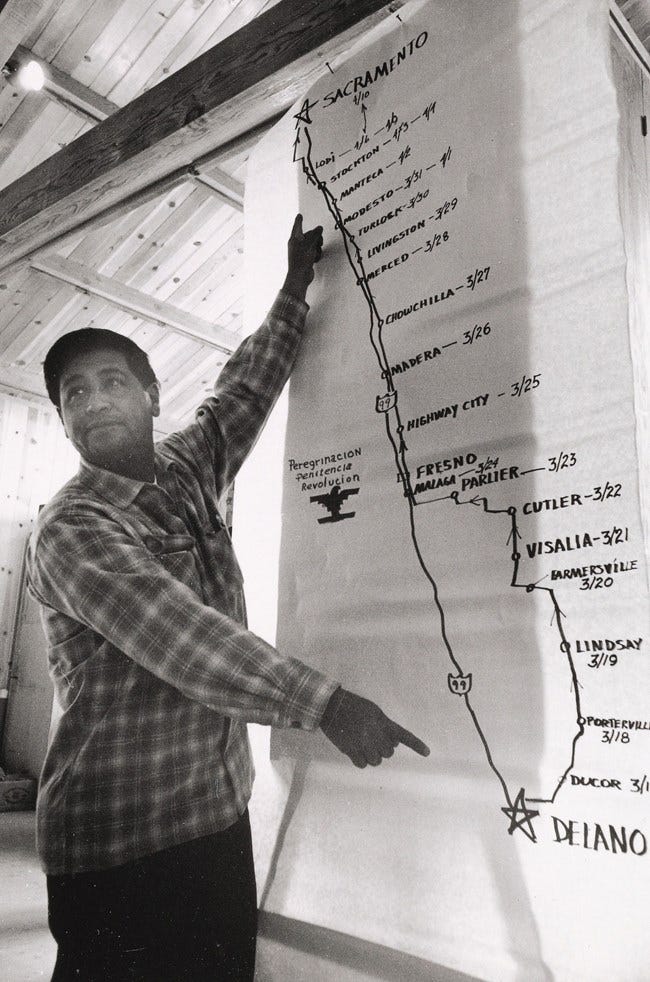

After joining the UFW [United Farm Workers], were you on the famous 300-mile march from Delano to Sacramento?

MARSHALL GANZ:

That was my first assignment—to set up an organization in Bakersfield. Then I was coordinator of the march, though we called it a pilgrimage. Our slogan was, in Spanish: “Pilgrimage, Penance, Revolution.”

JON:

This was a big deal in the mid-1960s. Cesar Chavez was on the cover of every magazine.

MARSHALL GANZ:

It was the convergence of a political, economic and moral strategy for mobilizing both the public and our own people. This is where Bobby Kennedy comes in. He was on the Senate Labor subcommittee and came out to hold hearings, which was a big event. He became a real ally, and part of it was a Catholic thing. Part of it was his own politics. Kennedy called out the sheriff and made an ass out of him. And we timed the start of the march for the next morning so the press would be there.

We started the march and police deployed to stop us and they look just like fucking Selma, Alabama.

JON:

The fasting that Chavez was doing was a brilliant stroke.

MARSHALL GANZ:

It was kind of controversial within the UFW. Some people thought it was grandstanding, but it turned out to be hugely effective.

JON:

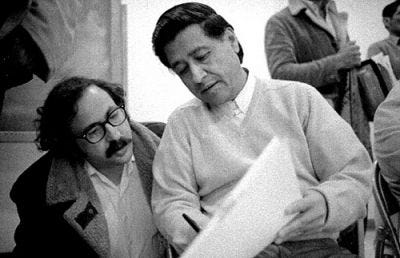

Can you tell me more about Chavez personally?

MARSHALL GANZ:

Cesar was an autodidact. When I met him, he was reading Churchill’s The Gathering Storm because he wanted to understand Gandhi’s opponent and learn how Churchill operated. He would read everything as a manual, like Gandhi, gleaning ‘“experiments in truth” – having begun with the Lives of the Saints. He had a brilliant capacity for this. And at first, he was modest. Not a big flourishing speaker. No big cars, just the opposite.

JON:

So what happened to him? When did he start to go off the rails and how painful was it?

MARSHALL GANZ:

Extremely painful. Cesar was always a little weird. I’m using the word sort of humorously, but he would look at things differently or see possibilities or try things— try just eating broccoli for [months]. There was this experimental approach to things.

JON:

When did Chavez turn into kind of a Maoist—and go around the bend?

MARSHALL GANZ:

I wouldn’t call him a Maoist. He fell victim to what Rod Kramer calls “political paranoia”. Well, here’s the story. We win in 1970 with the grapes boycott. And then we get into a fight with the Teamsters in Salinas Valley. And so there’s a whole period where the Catholic Church is trying to mediate. But it breaks down and so we go on strike in Salinas. We win four contracts, which was a big fucking deal. But in 1973, when the original great contracts were up, the growers shifted to the Teamsters. And so all of a sudden the contracts that were the base of the union were gone. All this is happening in a domain in which there is no labor legislation. And so we got into this really tough strike starting in Coachella and Bakersfield which we turned into another boycott when two of our strikers – Naji Daifullah and Juan de la Cruz – were murdered in just two days – one, beaten to death by a Kern county Deputy Sheriff and the other shot through the heart by a strike breaker.

Finally, in 1975, after two years of boycotting, wildcat striking, inflicting overtime costs on counties, and the election of Jerry Brown as Governor, we had built enough power to win the first law facilitating unionization of farm workers in the continental United States. And in August, when the law went into effect, we had to organize literally hundreds of representation elections – against the Teamsters and/or the growers – across the entire state. This began creating tensions within the union as to who had learned to do the organizing to win elections, and who hadn’t. Uncharacteristically for a person who loved organizing as he did, and learning, he began stepping back from the whole thing, going on a long march up and down California, but oddly withdrawn from the new organizing challenges we had to learn to meet.

There were so many elections that the Labor Board ran out of money and had to shut down after just 5 months when the California Legislature, led by some San Joaquin Valley Democrats, refused more funding. As a result, we qualified for a ballot initiative on the November ballot, and even after the Legislature had renewed the funds, we went ahead with it, Proposition 14. We lost. It was the first time we’d had a big public loss like that, and Cesar seemed to take it really hard. And after that, it started being really weird, with mind control experiments. It was as if he lost the core confidence that he had. He developed a negative image of himself. At first, people would say, “Oh, he’ll get over it.” The next turning point was 1978 when the lawyers—who were paid very little—wanted a salary increase. We had a board vote and it split five to four, Cesar took the position that everyone should be a volunteer—no salaries at all.

That’s when he tried to introduce “the Game.”

JON:

“The Game” was a series of purges?

MARSHALL GANZ:

No, the Game was a therapeutic method, started as a drug rehab program Synanon. There would be a circle and someone would start off accusing somebody of something and then that person had to figure out how to defend themselves. And soon they tried to turn it on somebody else. I guess the theory was that you learned how you had to engage, or whatever. But in a political – or cult – context in which Synanon founder, Chuck Deitrich had begun to use it, was just a control device. Really evil. And Deitrich befriended Cesar who was struggling to assert some kind of control.

Cesar really lost it, getting worse and worse. Most of the leadersshp who had built the union resigned or were “purged”. And, even after we left, there were some pretty direct anti-Semitic attacks on me and on Jerry Cohen, former general counsel-accusing us of conspiring to destroy the union. The whole thing just went into a deep, awful dark place.

JON:

To return to today: Where we are right now as a democracy and what can organizing do to protect us?

MARSHALL GANZ:

“If not now, when?” means you don’t figure out how to solve these problems without solving them. In other words, you have to act because you haven’t acted if you wait till you have it all figured out.

JON:

Maybe I’m being Pollyannish, but I think that there’s a core of Democrats who can be convinced to, as I like to put it, stop wringing their hands and start ringing doorbells— and tap their long suppressed eagerness to go out and meet people face-to-face. In a short time, with the help of social media, activists could create a fairly large-scale Democracy Project, or something like that.

MARSHALL GANS:

Yes, they could.

JON:

To change the subject, just this month, Amazon workers voted to unionize at the Staten Island location. How soon will we be able to tell whether this is a landmark moment in the resurgence of the labor movement or just an isolated piece of good news?

MARSHALL GANS:

It depends on what labor organizers learn from it, act on what they learn, and commit to sticking with it. It also depends on the extent to which this sparks similar efforts in other places. Although each Starbucks’ unit is far smaller, the number of units seems to be growing faster.

JON:

What should they do to keep the momentum going in contract talks?

MARSHALL GANS:

Keep organizing. Use contract talks to continue organizing the work force. The outcome will depend more on what they bring to the table than what happens at the table. Jane [McAlevey] has written a wonderful chapter on how she did this with Vegas hospitals.

JON:

Is it easier or harder to organize $25 an hour workers than farm workers?

MARSHALL GANS:

It all depends. Although wages matter, of course, people are more often sparked to organize in reaction to disrespect, abusive supervision, predatory behavior, and favoritism. The tension between what I perceive my own value to be and the kind of treatment I’m receiving is critical. Good organizing doesn’t just attack “the boss” but it raises people’s sense of their own worth, their collective power, and their sources of hope — and the way management practices are in conflict with this.

JON:

Thanks, Marshall.