The Power of Story in Social Movements – Prepared for the Annual Meeting of the American Sociological Association, Anaheim, California (Working Paper)

Paper by Marshall Ganz about the power of story in social movements with a case study of the farmworkers movement in the 1960s.

This story shall the good man teach his son;

And Crispin Crispian shall ne’er go by,

From this day to the ending of the world,

But we in it shall be remember’d;

We few, we happy few, we band of brothers;

For he to-day that sheds his blood with me Shall be my brother;

be he ne’er so vile,

This day shall gentle his condition:

And gentlemen in England now a-bed

Shall think themselves accursed they were not here,

And hold their manhoods cheap whiles any speaks

That fought with us upon Saint Crispin’s day.

Henry V, Act IV, Scene 3 William Shakespeare

Introduction

In this exemplary motivational speech, set on St. Crispin’s Day eve, King Henry tells a new story, a story promising identity transformation for all who choose to take part in the impending battle with the French, by whom they are vastly outnumbered. The outcome of the promise, however, depends on its efficacy generating what Henry and his men need to come out of the battle alive. Perhaps their long bows could give them superiority over the mounted, armored French, but only if they had the courage to stand and fight. In this paper I focus on the relationship between story and strategy in social movements – arguing a unique source of social movement power is in the new story it tells.

I came to my interest in story — and strategy — in three ways. As a child for whom the annual telling of the Passover story never ceased to be remarkable; as a youthful volunteer with SNCC in Mississippi who recognized a new telling of this familiar story; and as an organizer with the United Farm Workers who took part in yet a newer telling of this story. As a student of the sociology of social movements, concerned with a lack of focus on the actor centered aspects of the work, especially the influence of agents – leaders and participants – in making motivational and strategic meaning of why they should and how they can mobilize resources to take advantage of opportunities. And as a teacher of practitioners of organizing who has discovered teaching about story to be among the most useful teaching I do.

How Social Movements Story

I began this paper with Henry V, an illustration of the link between telling a good story and devising a good strategy. Sadly social movement scholars in the political process tradition have largely ignored the interpretive work of story telling, focusing instead on more structural matters of resources and opportunities.1 The one aspect of interpretive work social movement scholars have investigated is framing (McAdam 1996). Although framing – generating cognitive contexts within which data acquires meaning – is inherent in cognition, however, most of these scholars limit themselves to discourse analysis. They catalogue, dissect, and compare one frame with another, sometimes correlating types of frames with types of outcomes, rather than attending to who participates in framing and in what way, explicating framing processes, or evaluating the different contexts within which framing occurs. The implicit process in these analyses, however, is one in which organizers strategically “package” a message for an “audience” much as a campaign consultant would – a relatively minor element of the interpretive work that goes on in social movements (Benford 1997; Benford 2000).

A newer generation of scholars has begun to go beyond framing, recognizing that story telling may be what most distinguishes social movements from interest groups and other forms of collective action (Somers 1992) (Gamson 1992) (Somers 1994) (Franzosi 1997) (Polletta 1998) (Polletta 1998) (Steinberg 1999) (Hunt 2000) (Bolough 2000) (Goodwin, Jasper and Polletta 2001) (Davis 2002). Story telling is central to social movements because it constructs agency, shapes identity, and motivates action.

- Story telling is how we learn to exercise agency to deal with new challenges, mindful of the past, yet conscious of alternative futures (Bruner 1986) (Polkinghorne 1988) (Bruner 1990) (Bruner 1991) (Emirbayer and Mische 1998) (Amsterdam and Bruner 2000). It is not about following a script, but about choosing how to handle deviations from a script. Story telling engages us in an “emplotted” account of actors proceeding in legitimate ways toward valued goals who meet unexpected trouble, to which they must respond with innovative action leading to resolution along a new pathway, toward a new goal, or go down to defeat, from which a “moral” is drawn (Amsterdam 2000). They teach us how to deal with the unexpected, improvising alternative futures even while maintaining continuity with our past.

- Story telling is how we develop individual and collective identities that define the ends we seek and among whom we seek them (MacIntyre 1981) (Carr 1986) (Taylor 1989) (Bruner 1990) (Polkinghorne 1991) (Somers 1992) (Hunt 1994) (Somers 1994) (Ricoeur 1995) (Teske 1997) (Polletta 1998) (Davis 2000) (Gergan 2001) (Hincheman and Hincheman 2001) (MacIntyre 2001). Our identity can be understood as a story we weave from the lifetime of stories in which we have participated as tellers or listeners, learning how to act in the world. When we tell our story we do identity work, reenacting who we have been and forging the persons we become. As an interaction among speakers and listeners, story telling is culture forging activity, constructing shared understandings of how to manage the risks of uncertainty, anomaly, and unpredictability grounded in recollection of how we dealt with past challenges. Our individual identities are thus linked with those with whom we share stories – our families, communities, colleagues, faith traditions, nationalities – and with whom we enact them at our family dinners, worship services, holidays, and other cultural celebrations that institutionalize – or transform – their retelling

- Story telling is how we access the emotional – or moral – resources for the motivation to act on those ends (Brugeggemann 1978) (Sarbin 1995) (Bradt 1997) (Peterson 1999) (Peterson 1999). Inherently normative, stories map positive and negative valance onto different kinds of behavior. They thus become what Charles Taylor calls our “moral sources” – sources of emotional learning we can access for the courage, love, hope we need to deal with the fear, loneliness and despair that inhibits our action (Taylor 1989) (Jasper 1998). As St. Augustine taught “knowing the good” is insufficient to produce a change in behavior that requires “loving the good.” Story telling is both a way to “frame” our experience as purposive (making things “add up”) and of “regulating our emotions” (retaining confidence, keeping our anxiety under control, having a story we can believe in) (Bruner 1990).

In this paper I explore the influence of story telling in the launching of the farm worker movement led by Cesar Chavez over the course of a four-year period from the spring 1962 to the spring of 1966.2 In particular I address the influence of story at three moments of choice, identity formation, and action: forming a leadership core, launching an organization, and launching a movement.

Forming the Leadership

The farm workers movement was launched in the spring of 1962 by a “happy few” of some 12 people who had come together during the 1950s, led by Cesar Chavez.3 Five were Mexican-Americans who no longer worked in the fields, but four of whom were children of the first generation of Mexican immigrant farm workers. The fifth, Dolores Huerta, was the daughter of a New Mexico mine union leader and Stockton boarding house operator. Four were Mexicans who had immigrated to work in the fields, one of whom had arrived without “papers.” They included three couples in which both partners were actively involved. None of the Latinos had attended high school, except for Huerta, who went to college, and most were active Roman Catholics. Of the three Anglos, two were Protestant clergymen in their 20s, graduates of Union Theological Seminary. The third, Fred Ross, the group’s elder at 56, a former teacher, social worker, and camp administrator, had been recruited by Saul Alinsky in 1947 to organize the Community Service Organization (CSO), the first statewide Mexican-American civic association in California. Ross recruited Chavez in 1952. And together they recruited the others.

Having lived the conditions they hoped to change, the Latinos recruited into CSO, learned to focus their anger politically, developing a new sense of agency as they came to think of themselves as “organizers.” By organizing they had curbed police brutality, expanded the voter roles, won pension benefits for non-citizens, but had done little to improve the lot of the farm workers, the community from which most had come. Led by Chavez, whose plan to organize farm workers the more cautious CSO board rejected, they decided to do it themselves. Relying on his savings, help from friends, and what his family could earn in the fields, Chavez rejected outside financial help and moved to Delano to begin.

Launching the Organization

In the spring of 1962, Chavez and his collaborators launched a six month house meeting drive among San Joaquin Valley farm workers, beginning with those who had been active in CSO, and soliciting hundreds of individual stories of injustice, reweaving them into a broader story of economic, racial and political injustice, rooted in the history of Mexican farm workers in the US.5 This story, in turn, was rewoven with those of CSO, an American civic association, the Mexican “revolutionary” tradition, and Roman Catholic social teaching into a vision of a new organization that offered hope of tackling these injustices, opening the way to a new future.

This new story was formalized at a “founding convention” of some 200 farm worker delegates held in the banquet hall of a Fresno Mexican restaurant in September. Chavez chaired the meeting in Spanish, but modeled on CSO meetings, it included an invocation, pledge of allegiance, Roberts’ Rules of Order, official minutes, and election of officers. Delegates voted to organize, lobby for a minimum wage of $1.50/hour, establish dues of $3.50/ month, adopt the audacious red, white and black “farm worker eagle” flag, and the motto of “Viva La Causa.” Chavez claimed legitimacy for the new organization by reporting that during the house meeting drive, some 25,000 farm workers had registered in a census calling for better conditions. The three guests who addressed the meeting were drawn from communities being woven into the story of the new organization: Roman Catholic Fr. Cown of Del Rey, Rev. Hartmire of the Migrant Ministry, and Jose Corea, National President of the CSO. The dues were intended to create a death benefit, credit union, farm worker cooperative, and social services. The new organization named itself the Asociación de Trabajadores Campesinos, Farm Workers Association. Organizers proposed Asociación — not union — to avoid turning away workers with negative experience of earlier unionization attempts or provoking premature reaction from the growers. Campesino was descriptive of the Mexican peasantry, whose movement since the Revolution was evocative of land, dignity, and resistance. Towards the end of the meeting an original ballad in the Mexican heroic tradition was performed, “El Corrido del Campesino.”

Three months later they reconvened in a “constitutional convention” at Our Lady of Guadalupe Church Hall in Delano to hear the preamble of their constitution, drawn from Pope Leo XIII’s Encyclical Rerum Novarum, which read:

Rich men and masters should remember this – that to exercise pressure for the sake of gain upon the indigent and destitute, and to make one’s profit out of the need of another, is condemned by all laws, human and divine. To defraud anyone of wages that are his due is a crime which cries to the avenging anger of heaven.

Launching the Movement

On September 8, 1965, three years after its founding, NFWA leaders were forced to decide whether to join a grape strike initiated by Filipinos associated with a rival AFL-CIO union. Aware of the danger of acting to soon, but sensing opportunity, and willing to take some risks, they decided to test support among Mexican workers by mobilizing strike vote. To invoke their shared religious and cultural narratives – or moral traditions – they scheduled the meeting for the hall of Our Lady of Guadalupe Church on September 16th, Mexican Independence Day. But Chavez also recognized the opportunity afforded by the new story of the civil rights movement unfolding across the country, introducing it at the strike vote by insisting on a commitment to nonviolence, a novelty in the farm worker world. He also asked for a commitment to pursue the strike to win union recognition, not only a wage increase, another new expectation for many of those present. Eliseo Medina, then an 18 year-old farm worker, remembers:

Then they call a meeting for Our Lady of Guadalupe on September 16. Everybody’s full of revolutionary fervor. So I go to the meeting. Even though I didn’t like church much. It’s packed. I’d never met Cesar Chavez. I didn’t know what the hell he looked like. Padilla . . . introduces him and he’s a little pipsqueak. That’s Cesar Chavez? He wasn’t a great speaker, but he started talking and made a lot of sense. We deserved to be paid a fair wage. Because we’re poor we shouldn’t be taken advantage of. We had rights too in this country. We deserve more. The strike wouldn’t be easy. The more he said how tough it would be the more people wanted to do it. By time the meeting ended…that was it for me (Medina 1998.).

The 1,000 enthusiastic Mexican workers who attended the meeting voted overwhelmingly to go on strike. The organizers hoped to turn the strike into a movement. Adapting their own version of the civil rights story in the “strike issue” of the newspaper, they wrote:

What is a movement? It is when there are enough people with one idea so that their actions are together like the huge wave of water, which nothing can stop. It is when a group of people begins to care enough so that they are willing to make sacrifices. The movement of the Negro began in the hot summer of Alabama ten years ago when a Negro woman refused to be pushed to the back of the bus. Thus began a gigantic wave of protest throughout the South. The Negro is willing to fight for what is his, an equal place under the sun. Sometime in the future they will say that in the hot summer of California in 1965 the movement of the farm workers began. It began with a small series of strikes. It started so slowly that at first it was only one man, then five, then one hundred. This is how a movement begins. This is why the Farm Workers Association is a movement more than a union.(Malcriado 1965)

Although many workers left the area, growers began to recruit strikebreakers from the outside to replace them and responsibility for maintaining roving picket lines to inform the new arrivals of the strike fell to a cadre of some 200 strikers and volunteers. Lacking a strike fund, strikers also had to rely on outside contributions from supporters for sustenance for themselves and their families. By the second week of the strike, the NFWA developed a routine of Friday night meetings and Saturday delegations to sustain these activities.

The Friday night meetings, conducted by Chavez, were a two-hour weekly celebration of a new chapter in the strike story – told in reports, skits, and songs. About 200 strikers, their families, volunteers, and visiting religious, student, labor and community delegations regularly packed a small social hall for inspirational reports, interpreting the week’s events. The actos of the Teatro Campesino, led by Luis Valdez, which combined elements of Mexican folk theater, Commedia del Arte, Bertholt Brecht, and the San Francisco Mime troupe, offered comic reflections on interactions among workers, growers, contractors, strike breakers, organizers, and supporters. Medina remembers:

I loved the Friday night meetings. They were like revivals. There was all this great fun, and reports and speeches. A strong sense of solidarity. We’re all in it together. Hearing people come from San Francisco, LA, places that I never even knew existed. It was all very new. It was like you never knew such things existed. People would come, and ministers and priests, and people from other places. And then they announced all these famous politicians and unions. . .Wow! I was like I was drinking fine wine (Medina 1998.).

Masses celebrated by “huelga priests” also became part of the weekly striker routine, affirming the value of sacrifice the strike required. Mexican history came alive as slogans began to appear on walls and fences that read: Viva Juárez, Viva Zapata, Viva Chavez! Strike strategy was devised in meetings among organizers, but the motivational work on the story of the strike—without which there would have been little to strategize about—was told in the Friday night meetings.

This focus on ethnic identity also had benefits in the country as a whole. The systematic discrimination to which Mexicans had been subjected in the Southwest was a story not well known by the rest of the country, but NFWA leaders recognized the civil rights movement might have created an opportunity for telling this story to the rest of the country, explaining the dire circumstances in which farm workers lived and distinguishing the NFWA from “just another union” and the farm worker struggle from “just another strike.” The fact La Causa rooted its claims in Catholic social teaching also insulated it from “redbaiting” that had been so effective in scuttling farm union organizing efforts in the past and attracted Catholic clergy whose leaders were concluding their deliberations at Vatican II. Finally, the NFWA could reach out to farm workers who knew little of the benefits of unionization, but who recognized it as an effort by “Mexican people” to help themselves. It also meant the strike could draw economic, political, and moral support from Mexicans and Mexican-Americans in cities and towns throughout the state.

Although support for the strike continued to grow, in November the grape season had ended with no breakthroughs and a boycott called in December against Schenley Industries, a major liquor company with 4000 acres of grapes in Delano, had produced no results. In February, Chavez gathered an expanded leadership group together at a supporter’s home near Santa Barbara to devote three days to figuring how to move Schenley, prepare for the spring, and sustain the commitment of strikers, organizers and supporters. I quote from my notes of that meeting:

As proposals flew around the room, someone suggested we follow the example of the New Mexico miners who had traveled to New York to set up a mining camp in front of the company headquarters on Wall Street. Farm workers could travel to Schenley headquarters in New York, set up a labor camp out front, and maintain a vigil until Schenley signed. Someone else then suggested they go by bus so rallies could be held all across the country, local boycott committees organized, and publicity generated, building momentum for the arrival in New York. Then why not march instead of going by bus, someone else asked, as Dr. King had the previous year. But it’s too far from Delano to New York, someone countered. On the other hand, the Schenley headquarters in San Francisco might not be too far — about 280 miles which an army veteran present calculated could be done at the rate of 15 miles a day or in about 20 days

But what if Schenley doesn’t respond, Chavez asked. Why not march to Sacramento instead and put the heat on Governor Brown to intervene and get negotiations started. He’s up for re-election, wants the votes of our supporters, so perhaps we can have more impact if we use him as “leverage.” Yes, some one else said, and on the way to Sacramento, the march could pass through most of the farm worker towns. Taking a page from Mao’s “long march” we could organize local committees and get pledges not to break the strike signed. Yes, and we could also get them to feed us and house us. And just as Zapata wrote his “Plan de Ayala,” Luis Valdez suggested, we can write a “Plan de Delano,” read it in each town, ask local farm workers to sign it and to carry it to the next town. Then, Chavez asked, why should it be a “march” at all? It will be Lent soon, a time for reflection, for penance, for asking forgiveness. Perhaps ours should be a pilgrimage, a “peregrinacion,” which could arrive at Sacramento on Easter Sunday (Ganz 2000)

The march got underway on March 17, led by a farm worker carrying a banner of Our Lady of Guadalupe, the patroness of Mexico, portraits of campesino leader Emiliano Zapata, and banners proclaiming “peregrinación, penitencia, revolución”: pilgrimage, penance, revolution. Strikers also carried placards calling on supporters to boycott Schenley. Of 67 strikers selected to march the distance, the oldest, William King, was 63 and the youngest, Augustine Hernandez, was 17; eighteen were women. The march attracted wide attention, particularly when television images of a Delano police line in helmets and holding clubs blocked its departure as a “parade without a permit”, evoking images of police lines in Selma the year before. As the march progressed from town to town up the valley, public interest in the story grew, especially after more than 1,000 people welcomed the marchers to Fresno at the end of the first week. What would happen? Would they get what they want? Daily bulletins began to appear in the Bay Area press, stories about who the strikers were, why they would walk 300 miles, what the strike was all about. Roman Catholic and Episcopal bishops authorized their faithful to join the pilgrimage and the Northern California Board of Rabbis came to share Passover matzoh with the marchers. The march articulated not only the farm workers’ call for justice, but also claims of the Mexican-American community for a new voice in public life. And at an individual level Chavez described the march as a way of “training ourselves to endure the long, long struggle, which by this time had become evident…would be required. We wanted to be fit not only physically but also spiritually…”[Levy, 1975. #90].

Then, on the afternoon of April 3, a week before they were due to reach Sacramento, Chavez received a call from Schenley’s lawyer. Schenley had begun to feel the effects of the boycott. Fearful the arrival of the marchers in Sacramento would become a national anti-Schenley rally, they wanted to settle. Hurried negotiations produced recognition of the farm workers union, substantial immediate improvements in wages and working conditions, and the first real union contract in California farm labor history. But even as the marchers cheered their victory, they turned over their “Boycott Schenley” signs to write “Boycott S&W”, “Boycott Treesweet”, products of powerful DiGiorgio Corporation that would be their next target.

On Saturday afternoon, the growing company of marchers gathered on the grounds of Our Lady of Grace School in West Sacramento, on a hill looking across the Sacramento River to the capitol city they would enter the next morning, a scene more than one speaker compared to that of the Israelites camped across the River Jordan from the Promised Land. After a prayer service of some 2000 people, Roberto Roman, a farm worker who had carried a 2×4 wooden cross draped in black cloth 300 miles from Delano to Sacramento, stayed up most of the night redraping it in white and decorating it with flowers. The next morning, barefoot, he bore his cross triumphantly across the river bridge, down the Capitol mall, and up the Capitol steps where he was joined by 51 other “originales” who had completed the entire march and a crowd of 10,000 farm workers and supporters. Although the speakers included a panoply of religious, labor, political and Mexican-American leaders, they did not include Governor Brown. He had decided to “spend the day with his family” at Frank Sinatra’s house in Palm Springs. In all the excitement over Schenley, the fact the Governor failed to meet with the marchers seemed less important. The Mexican-American community, however, took it as a direct affront—a fact that gave the Chavez new bargaining chips with the Governor that would become very important in the next chapter of the struggle.

Interpretation

What does story telling do? How does it create agency, how does it form and reform identity, and how does it motivate action? What difference does this make in explaining the origins, development, and outcomes of social movements?

The “happy few” who launched the farm worker movement had developed their individual and collective identity narratives in what Margaret Somers (Somers 1994) calls the “relational context” of the CSO, grounded in shared cultural and religious traditions, leavened by the immigrant farm worker experience, and enhanced by choices they made through which they became “organizers’ not only able – but obligated – to change their communities. It is easier to understand the source of their commitment in terms of their stories of who they had become (Teske 1997), than in terms of material, purposive, or status incentives it was in their interest to pursue (Wilson 1974 (1995)). This can also help elucidate a mystery that baffles rational choice scholars of where what they call zealots or unconditional cooperators come from that they acknowledge start social movements, but can’t account for (Coleman 1990) (Chong 1991) (Munck 1995) (Kim 1997).

What is more, their stories could engage others whom they hoped to recruit, leading to the founding convention that formalized the transformation of thousands of individual stories into a shared story of a new organization. Founding the new organization blended the Mexican religious, political, and cultural narratives central to the identities of leaders and participants with an American tradition of civic associationism, combining the familiar with the novel in a way that makes a good story. And the benefits the new organization hoped to offer– a credit union, a death benefit, and social services — would not only be of value in their own right, but provide important evidence of the new story the solidarity, dignity, and power it could mean to be a Mexican farm worker in California.

As the strike unfolded, the NFWA learned to tell its story daily through picket lines, strikers meetings, civil disobedience, support delegations, religious celebrations, and, of course, the march to Sacramento. A “charismatic community” thus emerged based on “vows of voluntary poverty” that shared a religious commitment to winning the strike. This striker community became a crucible of cultural change that gave rise to new shared identities. Farm workers became Chavistas, supporters, voluntarios; the grape strike, La Huelga; the NFWA, La Causa; and Cesar Chavez. . . became Cesar Chavez, the legendary farm worker leader. The march was story telling in action, words and symbols. It enacted an individual and collective journey from slavery to freedom. By choosing to take part, individuals could link their identity with those of others who shared “la causa”, entering upon the stage of history. The march didn’t simply afford the NFWA an opportunity to tell its story, but was an enactment of its story, in a way in which workers, supporters, and public could participate. This cultural dynamic infused the NFWA with significance for farm workers, Mexican-Americans, students, religious activists, and liberal Americans far beyond its political reach or economic influence as a community organization. But because, like King Henry’s promise, the march was such a powerful story, it was also a powerful strategy: a way to mobilize support for the first boycott that resulted in a breakthrough that, in turn, enshrined the march with the still greater significance of an enacted story of how Mexican farm workers through sacrifice, solidarity, determination — and good organizing – could change their world and themselves.

Conclusion

I began this paper with Henry V, an illustration of the link between telling a good story and devising a good strategy. I’ve tried to show how story telling can develop agency, reformulate identity, and afford access to the motivational resources to form a leadership group, found a new organization, and launch a new social movement. Although we can look at stories as discursive structures, the aspect most clearly shown here is story telling as performance – in which the “text” is action as well as word and symbol. Appreciating the role of story requires attending to the performance — who is telling the story, with whom they are interacting, where and when stories are told. Arguably the most critical elements in telling a new story are the identities of storytellers and listeners. The identity of a storyteller gives credibility to the story, linking her with her listeners in a common journey. Social movements tell a new story. In this way they acquire leadership, gain adherents, and develop a capability of mobilizing needed resources to achieve success. Social movements are not merely reconfigured networks and redeployed resources. They are new stories of whom their participants hope to become.

References

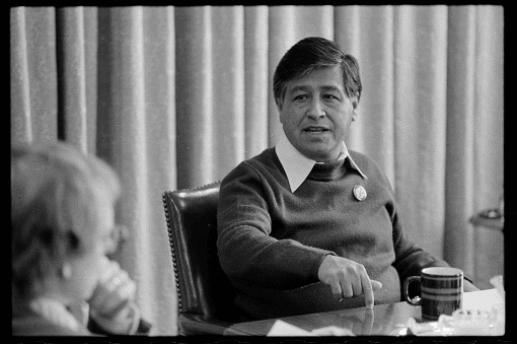

Image source – Trikosko, Marion S, photographer. Interview with Cesar Chavez. 4/20/. Chavez talking and pointing downwards. , 1979. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2016646409/

Access Resource