Creating Shared Strategy: How to Strategize

An introduction to organizing and how to create shared strategy based on the works of Marshall Ganz.

Introduction

This excerpt of Creating Shared Strategy is from Marshall Ganz’s Framework PEOPLE, POWER AND CHANGE, pgs 16 – 23 and has been modified by Jacob Waxman.

The first step is to identify the people whom you are organizing, your constituency, and map out the other relevant actors. The second step is to come up with the goal of your organizing effort: what exactly is the problem is you hope to solve, how would the world look different if it were solved, why hasn’t that problem been solved, what would it take to solve it, and toward what clear, observable, and motivational goal could members of your constituency focus their work to get started, build their capacity, and develop their leadership? The third step is to figure out how your constituency could turn resources it has into the power it needs to achieve that goal: what tactics could it use, how could they target their efforts, and how would they time their campaign.

Strategy is “turning resources you have into the power you need to get what you want – your goal.

• Strategic Goal (what you want): The goal is a clear, measurable point that allows you to know if you’ve won or lost, and that meets the challenge your constituency faces.

• Power (what you need): tactics through which you can turn your resources into the capacity you need to achieve your goal.

• Resources (what your constituency has): time, money, skills, relationships, etc.

How Strategy Works

Strategy is Motivated: What’s the problem?

We are natural strategists. We conceive purposes, encounter obstacles in achieving those purposes, and we figure out how to overcomes those obstacles. But because we are also creatures of habit, we only strategize when we have to: when we have a problem, something goes wrong, something forces a change in our plans. That’s when we pay attention, take a look around, and decide we have to do something differently. Just as our emotional understanding inhabits the stories we tell, our cognitive understanding inhabits the strategy we devise.

Strategy is Creative: What can we do about the problem?

Strategy requires developing an understanding of why the problem hasn’t been solved, as well as a theory of how to solve it, a theory of change. Moreover because those who resist change often have access to more resources, those who seek change often have to be more resourceful. We have to use this resourcefulness to create the capacity – the power – to get the problem solved. It’s not so much about getting “more” resources as it is about using one’s resources smartly and creatively.

Strategy is a Verb: How can we adapt as we learn to solve the problem?

The real action in strategy is, as Alinsky put it, in the reaction – by other actors, the opposition, and the challenges and opportunities that emerge along the way. What makes it “strategy” and not “reaction” is the mindfulness we can bring to bear on our choices relative to what we want to achieve, like a potter interacting with the clay on the wheel, as Mintzberg describes it.

Although our goal may remain constant, strategizing requires ongoing adaptation of current action to new information. Something worked better than we expected. Something did not work that we had expected. Things change. Some people oppose us so we have to respond. Launching a campaign only begins the work of strategizing. This is one reason your leadership team should include a full diversity of the skills, access to information and interests needed to achieve your goal. We call this “strategic capacity.” So strategy is not a single event, but an ongoing process continuing throughout the life of a project. We plan, we act, we evaluate the results of our action, we plan some more, we act further, evaluate further, etc. We strategize, as we implement, not prior to it.

Strategy is Situated: How can I connect the view in the valley with the view from the mountains?

Strategy unfolds within a specific context, the particularities of which really matter. One of the most challenging aspects of strategizing is that it requires both a mastery of the details of the “arena” in which it is enacted and the ability to go up to the top of the mountain and get a view of the whole. The power of imaginative strategizing can only be realized when rooted within an understanding of the trees AND the forest. One way to create the “arena of action” is by mapping the “actors” are that populate that arena.

Key Strategic Questions

1. Who are my PEOPLE?

2. What CHANGE do they seek? (Goal)

3. Where can they get the POWER? (Theory of Change)

4. Which TACTICS can they use?

5. What is their TIMELINE?

Step One: Who are my people?

Constituency

Constituents are people who have a need to organize, who can contribute leadership, can commit resources, and can become a new source of power. It makes a big difference whether we think of people with whom we work as constituents, clients, or customers. Constituents (from the Latin for “stand together”) associate on behalf of common interests, commit resources to acting on those interests, and have a voice in deciding how to act. Clients (from the Latin for “one who leans on another”) have an interest in services others provide, do not contribute resources to a common effort, nor do they have a voice in decisions. Customers (a term derived from trade) have an interest in goods or services that a seller can provide in exchange for resources in which he or she has an interest. The organizers job is to turn a community – people who share common values or interests – into a constituency – people who can act on behalf of those values or interests.

Leadership

Although your constituency is the focus of your work, your goal as an organizer is to draw upon leadership from within that constituency – the people with whom you work to organize everyone else. Their work, like your own, is to “accept responsibility for enabling others to achieve purpose in the face of uncertainty.” They facilitate the work members of their constituency must do to achieve their shared goals, represent their constituency to others, and are accountable to their constituency. Your work with these leaders is to enable them to learn the five organizing practices you are learning: relationship building, story telling, structuring, strategizing, and action. By developing their leadership you, as an organizer, not only can get to “get to scale.” You are also creating new capacity for action – power – within your constituency. For the purpose of this exercise your group here is your leadership team.

Opposition

In pursuing their interests, constituents may find themselves to be in conflict with interests of other individuals or organizations. An employers’ interest in maximizing profit, for example, may conflict with an employees’ interest in earning a comfortable wage. A tobacco company’s interests may conflict not only with those of anti-smoking groups, but of the public in general. A street gang’s interests may conflict with those of a church youth group. The interests of a Republican Congressional candidate conflict with those of the Democratic candidate in the same district. At times, however, opposition may not be immediately obvious, emerging clearly only in the course of a campaign.

Supporters

People whose interests are not directly or obviously affected may find it to be in their interest to back an organization’s work financially, politically, voluntarily, etc. Although they may not be part of the constituency, they may sit on governing boards. For example, Church organizations and foundations provided a great deal of support for the civil rights movement.

Competitors and Collaborators

These are individuals or organizations with which we may share some interests, but not others. They may target the same constituency, the same sources of support, or face the same opposition. Two unions trying to organize the same workforce may compete or collaborate. Two community groups trying to serve the same constituency may compete or collaborate in their fundraising.

Other Actors

These are individuals and actors who may have a great deal of relevance to the problem at hand, but could contribute to solving it, or making it harder to solve, in many different ways. This includes the media, the courts, the general public, for example. Mapping the actors can help us identify those who may be responsible for the problem our constituency faces, where they can find allies, and who else has an interest in the situation.

Step 2: Where can they get the power: Theory of Change?

Figuring out how to achieve a strategic goal – or even what goal is worth trying to achieve – requires developing a “theory of change? We all make assumptions about how change happens. Some people think that sharing information widely enough (or “raise awareness”) about a problem will change things. Others contend that if we just get all the “stakeholders” into the same room and talk with each others we’ll discover that we have more in common than that separates us and that will solve the problem. Still others think we just need to be smarter about figuring out the solution.

Community organizers focus on the community, their constituency, because they believe that unless the community itself develops its own capacity to solve the problem, it won’t remain solved. Another word for “capacity” is “power” or, as Dr. King defined it “the ability to achieve purpose.” Power grows out of the influence that we can have on each other. If your interest in my resources is greater than my interest in your resources, I get some power over you – so I can use your resources for my purposes. On the other hand, if we have an equal interest in each other’s resources we can collaborate to create more power with each other to bring more capacity to bear on achieving our purposes than we can alone. So the question is how to proactively organize our resources to shift the power enough to win the change we want, building our capacity to win more over time? Since power is a kind of relationship, tracking it down requires asking four questions:

- What do WE want?

- Who has the RESOURCES to create that change?

- What do THEY want?

- What resources do WE have that THEY want or need?

If it turns out that we have the resources we need, but just need to use them more collaboratively, then it’s a “power with” dynamic. If it turns out that the resources we need have to come from somewhere else, then it’s a “power over” dynamic. So the question is how our constituency can use its resources in ways that will create the capacity it needs to achieve the goal.

IF we do this, THEN that will likely happen. Test this out with a series of “IfThen” sentences. Once your satisfied you are ready to articulate your organizing sentence:

We are organizing WHO to achieve WHAT (goal) by HOW (theory of change) to achieve what CHANGE

Step Three: What Change Do They Seek: Goals?

We then must decide on a strategic goal for our campaign by asking what exactly the problem is, how the world might look if it were solved, why it hasn’t been solved, and what it would take to solve it.

What’s the problem?

What exactly is the problem, in real terms, in terms of people’s every day life? Brainstorm your teams understanding of what the problem is with as much specificity as possible. Dig into it and go beyond the accepted answers.

How would the world look different if the problem were solved?

What happens if we fail to act? What is the “nightmare” that awaits – or may already be here? On the other hand, what could the world look like if we do act? What’s our realistic “dream”, a possibility that could become reality?

Why hasn’t the problem been solved?

If the world would look so much better for our people if the problem were solved, why hasn’t it been solved? Has no one thought of it? Did people try, but found they were meeting too much resistance? Did people not know how? Did they lack information? Did they lack technology? Would solving the problem threaten interests powerful enough to derail the attempts?

What would it take to solve the problem?

More information? Greater awareness? New tools? Better organization? Better communication? More power? What changes by what people would be required for the problem to be solved?

What’s the goal?

Toward what goal can we work that may not solve the whole problem, but that could get us well on the way: it would make a real change, could build our capacity, could motivate others, could create a foundation for what comes next. No one campaign can solve everything, but unless we can focus our efforts on a clear outcome we risk wasting precious resources in ways that won’t move us towards our ultimate goal. Here are some criteria to consider for a motivational, strategic organizing campaign goal—one that builds leadership and power:

1) Specific Focus: It’s concrete, measurable, and meaningful. If your constituents win, achieving this goal will result in visible, significant change in their daily lives. This is the difference between “our goal is to win reproductive justice” and “our goal is to ensure that every student has access to free, round the clock contraception on our campus.” We make progress on the first one by turning it into something that can be achieved by moving specific decision makers to reallocate resources in specific ways. Your constituency will need this focus to move into action.

2) Motivational: It has the makings of a good story. The goal is rooted in values important to your constituency, requires taking on a real challenge, and stretches your resources: It isn’t something you can win tomorrow. Think David and Goliath.

3) Leverage: It makes the most of your constituency’s strengths, experience and resources, but is outside the strengths, experience and resources of your opponent.

4) Builds Capacity: It requires developing leadership who can organize their own constituency to enhance the power of your organization. It offers multiple local targets or points of entry and organization.

5) Contagious: it could be emulated by others pursuing similar goals.

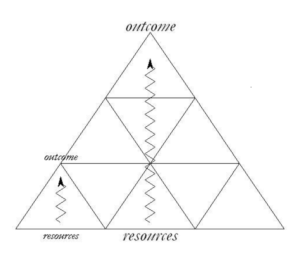

This pyramid chart offers a way to think about where the goal of your campaign can be nested within a larger mission in scope or in scale. At every level, strategy requires imagining an outcome, assessing resources available to achieve that outcome, and, in light of the context, devising a theory of change: how to turn those resources into the power needed to achieve that outcome, a theory that is enacted through tactics, timing, and targeting. In the bus boycott, planning the initial meeting required strategizing as much as figuring out how to sustain the campaign for the long haul. It is likely different people are responsible for different strategic scope at different levels of an organization or for different time periods, but good strategy is required at every level.

After agreeing upon criteria that make for a good strategic goal in your context, brainstorm again, generating as many possible goals as you can. Then evaluate them each against the criteria you’ve established. Then come up with an “if-then sentence”, imagining ways your constituents could use their resources to shift power in order to achieve their goals.

Step 4: What tactics can they use?

Remember what a “tactic” is? It’s the activity that makes your strategy real. Strategy without tactics is just a bunch of ideas. Tactics without strategy wastes resources. So the art of organizing is in the dynamic relationship between strategy and tactics, using the strategy to inform the tactics, and learning from the tactics to adapt strategy.

Your campaign will get into trouble if you use a tactic just because you happen to be familiar with it – but haven’t figured out how that tactic can actually help you achieve your goal. Similarly, if you spend all your time strategizing, without investing the time, effort, and skill to learn how to use the tactics you need skillfully, you waste your time. Strategy is a way of hypothesizing: if I do this (tactic), then this (goal) may happen. And like any hypothesis the proof is in the testing of it.

Criteria for good tactics include:

- Strategic: it makes good use of your constituency’s resources to make concrete, measurable progress toward campaign goals. Saul Alinsky and Gene Sharp are excellent sources of tactical ideas.

- Strengthens your organization: it improves the capacity of your people to work together.

- Supports leadership development: It develops new skills, new understanding, and, most importantly, new leadership.

There are two ways to operate in the world—you can be reactive, as many organizations are, or you can be proactive. In order to be proactive you have to set your own campaign goals and timeline, organizing your tactics so that they build capacity and momentum over time.

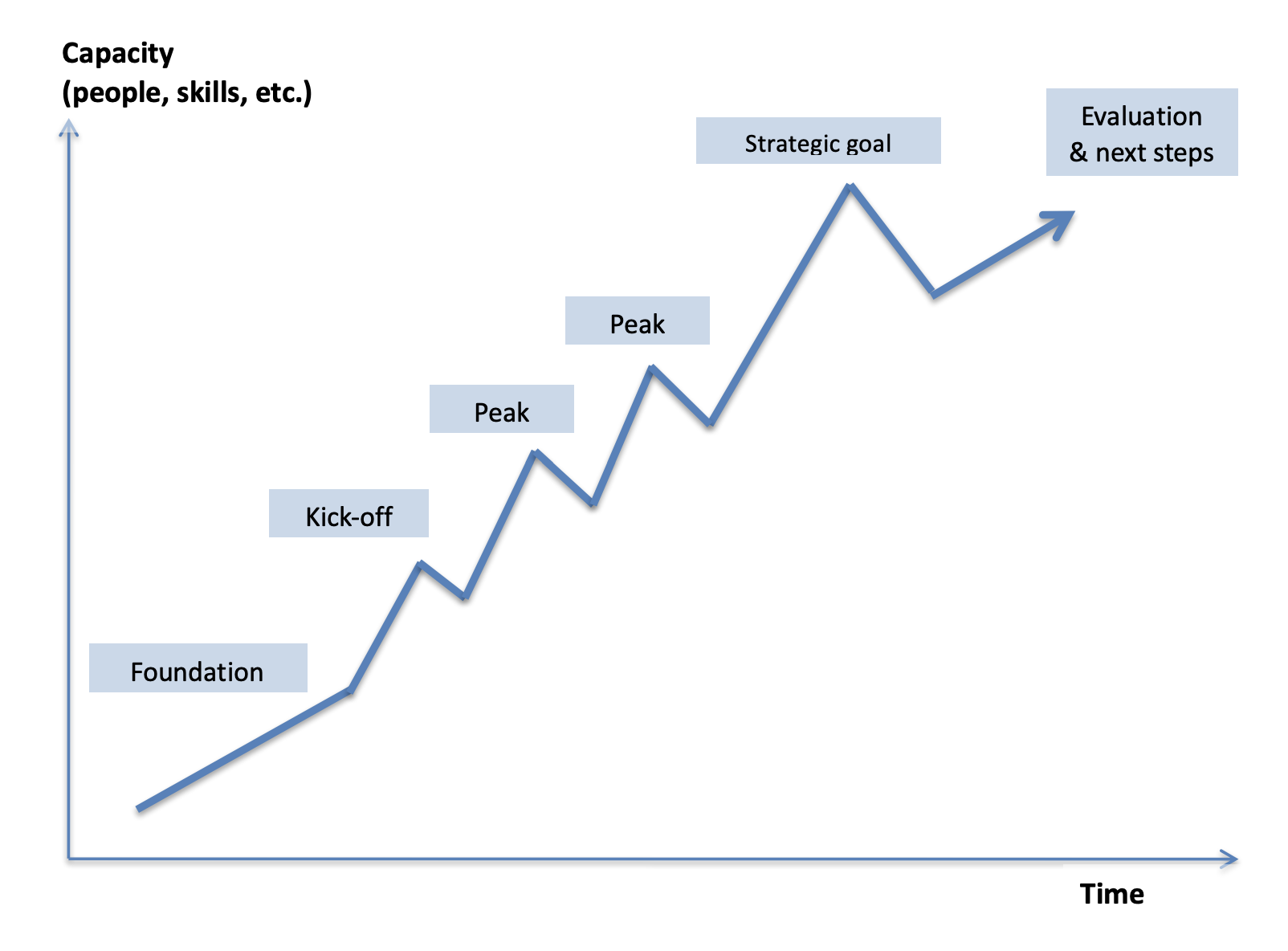

Step 5: What is their timeline?

The timing of a campaign is structured as an unfolding narrative or story. It begins with a foundation period (prologue), starts crisply with a kick-off (curtain goes up), builds slowly to successive peaks (act one, act two), culminates in a final peak determining the outcome (denouement), and is resolved as we celebrate the outcome (epilogue). Our efforts generate momentum not mysteriously, but as a snowball. As we accomplish each objective we generate new resources that can be applied to achieve the subsequent greater objective. Our motivation grows as each small success persuades us that the subsequent success is achievable – and our commitment grows.

A campaign timeline has clear phases, with a peak at the end of each phase—a threshold moment when we have succeed in creating a new capacity we can now put to work to achieving our next peak. For example, one phase might be a 2 month fundraising and house meeting campaign that ends in a campaign kickoff meeting or rally. Another phase might be 2 months of door-to-door contact with constituents affected by the problem you’re trying to solve, collecting a target number of petitions to deliver with a march on the Mayor at City Hall at the end, another peak. But within each phase there is a predictable cycle, which in a sense is a mini-campaign in itself: training, launch, action, more action, peak, evaluation. When organizing a peak, keep in mind a specific outcome that you want the peak to generate. For example, if you want to sign-up 50 new volunteers at an event or launch three neighborhood teams, how do you make that happen?

After each peak, your staff, volunteers and members need time to rest, learn, re-train and plan for the next phase. Often organizations say, “We don’t have time for that!”

Campaigns that don’t take time to reflect, adjust and retrain end up burning through their human resources and becoming more and more reactionary over time.