2020 Public Narrative Impact Survey Overview Report and Public Narrative in Action: Findings from the 2020 Public Narrative Impact Survey (Video)

Public Narrative Impact Survey Report and Video explores how public narrative is being used by individuals as a leadership practice within different domains, and the impact it has had on leadership development at the individual, community, societal, and institutional level.

Introduction

See how public narrative is being used in different ways in different contexts and countries. Here is a

- Report – 2020 Public Narrative Impact Survey Overview Report by Dr. Emilia Aiello and Marshall Ganz

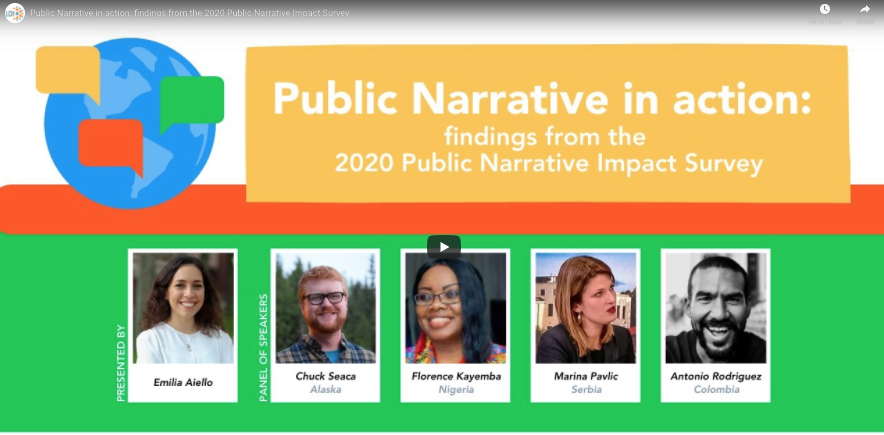

- Video – Public Narrative in Action: Findings from the 2020 Public Narrative Impact Survey. Dr. Emilia Aiello presents findings of the survey and a panel of speakers shares how they use public narrative in their work and communities.

2020 Public Narrative Impact Survey Overview Report – Summary

This report describes the results of the 2020 Public Narrative Impact Survey administered to individuals who learned public narrative in classrooms and in workshops between 2006 and 2020. Individual responses to the survey items provide data that will inform efforts to learn how public narrative is being used in different domains of usage (workplace, constituency groups, and campaigns; and within the private sphere, in interpersonal relationships such as family and friends), areas of societal action (e.g., advocacy/organizing in education, health, politics), and cultural and geographical contexts as well.

The 2020 Public Narrative Impact Survey is part of the research project Narratives4Change led by Dr. Emilia Aiello, funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement no. 841355. As part of this larger project, two research questions guided the survey.

- First, how is public narrative being used by individuals as a leadership practice within different domains of usage (e.g., workplace, constituency groups, campaigns, and within the private domain including family and friends)?

- Second, what impact does use public narrative have as reported by “users” at the individual, community, societal, and institutional level?

About Public Narrative

“Public narrative is a way of linking the power of narrative to the work of leadership by learning to tell a story of self, story of us, and story of now. Leadership is defined as “accepting responsibility for enabling others to achieve shared purpose under conditions of uncertainty.”

Narrative is a way we can access the emotional resources embedded in our values to transform threats to which we react fearfully and retreat into challenges to which we can respond hopefully and engage. Narrative is grounded in specific story moments in which a protagonist is confronted with a disruption for which s/he is not prepared, the choice s/he makes in response, and the resulting outcome.

Because we can identify empathetically with the protagonist, we experience the emotional content of the moment, the values on which the protagonist draws to respond. The “moral” of the story we learn, then, is in this emotional experience, a “lesson of the heart” rather than only a cognitive “lesson of the head.” We can thus call on this experience as a “moral resource” when we must face disruptions endemic to the human experience. As we begin to nest these particular story moments (beats) of our own within broader story moments (scenes) and these within broader moments (acts), we construct our own story, choices we made that mattered, and the values these choices express, a “story of self.”

We can also join with others in our family, community, nation, and faith to construct similar “stories of us” based on shared story moments. And we can interpret the present moment as one of urgent disruption to which we can respond drawing on our sources of hope, solidarity, and self-worth, rather than react influenced by our fears, isolation, and self-doubt. The former turns it in a challenge with which we can engage. The latter turns it into a threat from which we flee. Leaders can thus mobilize the emotional content of “public narrative” to communicate why it matters enough to us that we can do the cognitive strategizing to figure out how. Marshall Ganz and his collaborators began developing a pedagogy of this practice in 2006 and adapted it over the last 15 years in online and offline courses at the Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) and in workshops, projects, and campaigns such as the 2008 Obama for President campaign. Between 2006 to 2016, at least 32,184 people participated in 448 workshops in some 25 countries including Denmark, Serbia, Jordan, India, Viet Nam, China, Japan, Australia, and Mexico and in domains as distinct as health care, education, politics, religion, and advocacy.” pg. 1

Public narrative is used in diverse ways, most significantly in interpersonal communication. When used in the public sphere (beyond family and friends) public narrative is used in diverse ways, but contrary to the expectation that it is a form of public speaking used mostly to communicate among large audiences, it is especially useful in proximate interpersonal communication encounters such as one-on-one meetings, at work with colleagues, and teams in small groups. – M Ganz, E Aiello, 2021, p.3

Public narrative is considered to be extremely useful in the service of leadership in both general and specific ways. Almost 50% of survey respondents found public narrative to be “extremely useful” in their general leadership practice, and 40% said it has been very useful, across domains and learning context. – M Ganz, E Aiello, 2021, p.4

Download Report

2020 Public Narrative Impact Survey Overview Report

Watch Video

This video is available for LCN members with an active subscription.

Members log in to watch the video.

If you would like to become a member sign up here.

Dr. Emilia Aiello presents findings from the 2020 Public Narrative Impact Survey that explores how public narrative is being used by individuals as a leadership practice within different domains, and the impact it has had on leadership development at the individual, community, societal, and institutional level.

And a panel of speakers shared how they are using public narrative in their work and communities:

- Chuck Seaca from the Alaska Humanities Forum in the United States, working with youth and Indigenous communities in Alaska

- Florence Kayemba from Stakeholder Democracy Network in Nigeria, building public engagement on issues driving and enabling conflict in the oil rich region of the Niger Delta

- Marina Pavlic from Serbia on the Move and Kreni-Promeni in Serbia, organizing and mobilizing communities in campaigns on issues ranging from health policy to cultural norms

- Antonio Rodriguez from the Latin American Leadership Academy in Colombia, finding, developing and connecting young leaders across Latin America